Now, before you all jump up and shout “Yes! Next question!”, bear with me.

My friends and acquaintances will all know that I have a “Thing” (yes, with a capital T) about John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham. This “Thing” has grown and developed over the years since I found myself, somewhat to my own surprise, writing a novel about him.

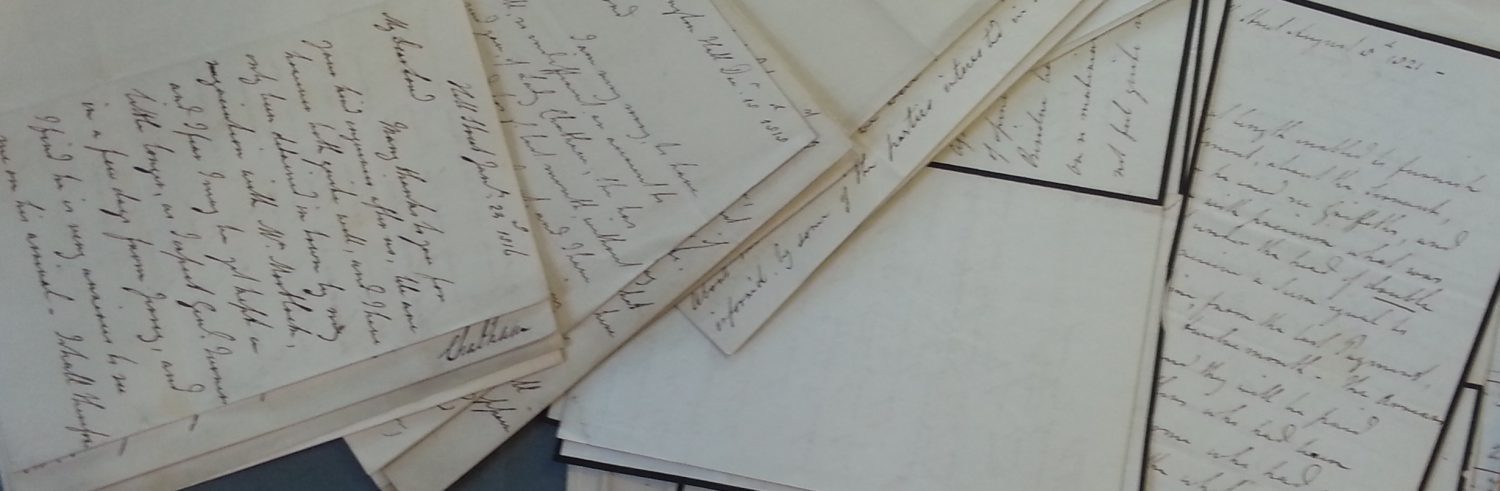

Perhaps I shouldn’t need to justify my choice of him as a subject, but sometimes I feel that I do. A few months ago I bought a letter off an antiques dealer written by John in 1802. I took it to an art shop to frame. “Very nice,” the man said as he measured it up for me. “But this Earl of Chatham…. what did he do?” This is a question I get asked a lot….

I think I mentioned before that Sir Tresham Lever in “The House of Pitt” wrote John off as “stupid and useless”. Most historians agree: he’s described, variously, as “intelligent but incurably idle” (Wendy Hinde, “Castlereagh” (London, 1981) p. 117); “charming and indolent, slightly over-burdened by the weight of his illustrious name … an incompetent general and a wretched administrator” (Joan Haslip, “Lady Hester Stanhope” (London, 1987) p. 23); “amiable … [but] exhibited signs of a natural lethargy which proved incurable” (Robin Reilly, “Pitt the Younger” (London, 1978) p. 10)… etc etc etc, you get the idea. Even Ehrman, while he admits John “was not untalented” (damned by faint praise!), reports the rumours of John’s slothfulness, drunkenness, incapacity and so on (John Ehrman, “The Younger Pitt: The Reluctant Transition” (London, 1983) p. 379.

I’m not yet ready to write my full “John was not as bad as all that” tirade (hence this is Part One only); that will have to wait till I’ve gone through all my notes. I think it is certainly beyond any historian to suggest that John was not so laid back he was pretty much horizontal. Lots of emotions complicated his relationship with his younger brother William (…. and let’s face it, being an impoverished older brother thoroughly dependent on his younger brother’s influence must have been a weird enough inversion of normality) but jealousy did not feature much, if at all. John was quite happy to let William reap all the political plaudits. Whether things would have been different had John not had a younger brother I do not know, but he never spoke once in the House of Lords that I can find and probably would not have got involved in politics at all had his brother not dragged him in.

So yes, lazy he almost certainly was. And yet when he was appointed to the Cabinet in 1788, as First Lord of the Admiralty, he seems (judging from the newspapers) to have knuckled down to the task with some degree of diligence. Cabinet meetings were held at his house (…. OK, maybe an excuse to be able to roll out of bed and go straight to work); he is often reported at Admiralty Board meetings; he was one of the Commissioners appointed during the Regency Crisis to draw up and present the Regency Bill to Parliament. He was a regular attender of court functions (and it seems George III quite liked him), not just the fun ones but the business ones too. Not, perhaps, a picture of overwhelming zeal, but certainly not one of a complete slacker.

So where did it start to go wrong? Ehrman traces it to the summer of 1793, in other words around the time when the First Coalition assault on the revolutionary French in Flanders was starting to go rather wrong. Chatham’s navy received the blame (along with the Duke of Richmond’s Ordnance) for not supplying the army well enough. Chatham defended himself by pointing out the government had split its pins between Flanders and Toulon, and the navy could not be expected to defend both fronts equally well. He escaped censure on that occasion, but when the Duke of Portland and his followers came over to Pitt from the Foxite side in the summer of 1794 they seem to have made it an express condition that one of their own would take over the Admiralty. Pitt held out five months; in December 1794 he moved his brother to the responsibility-lite post of Lord Privy Seal. Portland Whig Lord Spencer took Chatham’s place at the Admiralty.

Over the summer of 1794 I have seen a number of reports and rumours about John cropping up in newspapers and diaries (Ehrman refers to them, as I noted above). Was the Admiralty as badly run as was suggested? I’m afraid I haven’t done enough research to tell you. Rumour had it that John attended to no business before noon, kept naval officers waiting, and never opened his letters. I haven’t managed to trace any of these rumours to anything concrete (the one about the not opening letters, which is reported in N.A.M. Rodger, “The Command of the Ocean” (London, 2004) p. 363, I have traced to one of Spencer’s underlings, writing thirty or more years after the event). Obviously they all come from people who were not on John’s side, although that fact in itself means very little. As for John, he had little or no doubt he had been stabbed in the back by the Portland Whigs; he feared for his reputation, and it seems he has been right to do so.

What to conclude, therefore? John was not a naval man in any case. He was a military man, and (after Richmond resigned in early 1795) the only military man in a wartime cabinet. He seems to have given plenty of advice on military topics even when it wasn’t his remit: Castlereagh, for example, wrote to John requesting advice on military matters in October 1805 (Castlereagh Correspondence vol 6 (London 1851), 19). Lord Eldon famously said John was the ablest man in the Cabinet, and although it seems this was a throwaway remark I doubt he would have said it had he not thought John at least slightly clever. It is Chatham’s main misfortune that his whole life was blighted by the Walcheren campaign, which he commanded in 1809 and which ended in utter failure. That, however, is quite another story.

I don’t think I need to say here that I do not think John was a waste of space. You’ve worked that out by now, and 400 pages of novel certainly suggests I find him interesting. What I think is most interesting about him— to answer the question asked by the art dealer who framed my John letter— is not what he *did*, but *who he was*. He was a man who had the good fortune, or perhaps the ill fortune, to be the eldest son and elder brother of two very famous, important and brilliant public figures. He must have lived his entire life in their shadow. I hope to bring him out a bit, and round out the “late Lord Chatham” (as he was nicknamed) as a personality in his own right.

And that’s enough blathering on. Humour me. As I said, I have a Thing.