Apologies for being a day late, but I couldn’t access the blog yesterday. So here is Part 2 of Comedy Walcheren 1809. (For disclaimer and further context, see Part 1.)

***

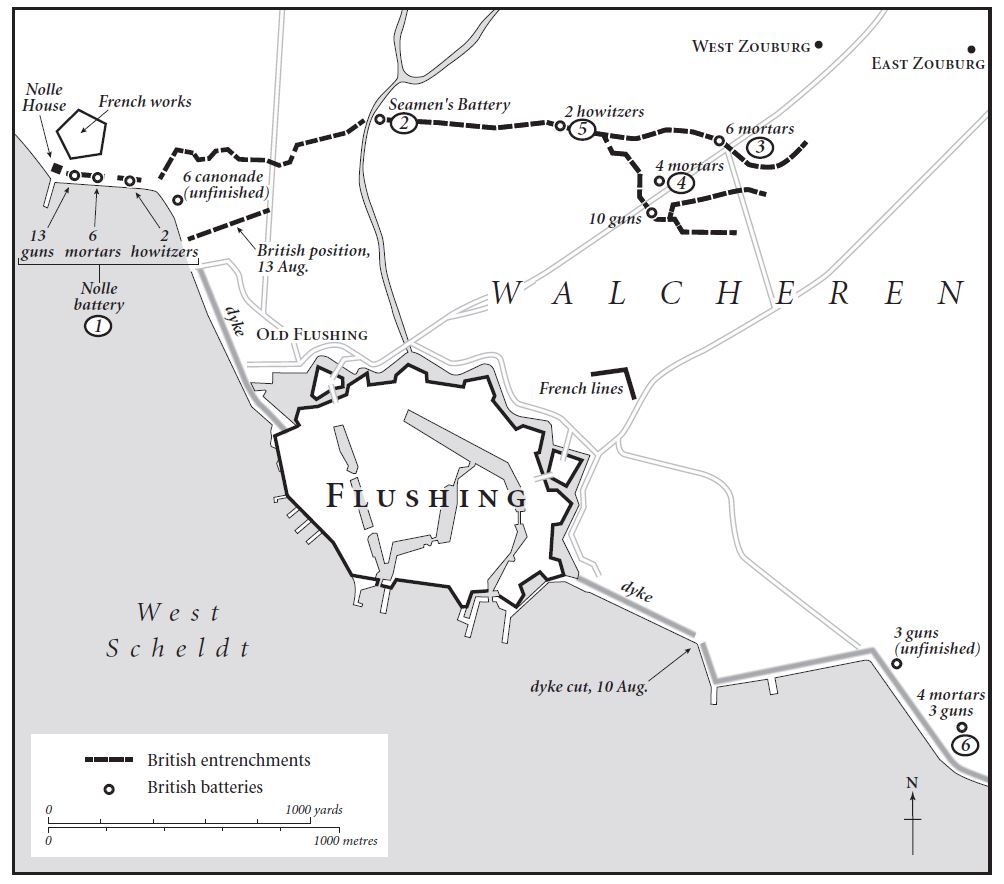

[After the fall of Flushing, August 1809]

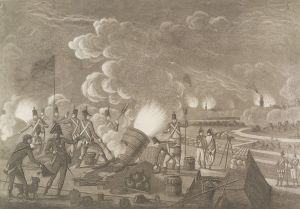

Flushing after the bombardment, from here

COOTE: Right. That went swimmingly. Shall we send in some commissioners to negotiate the surrender of the city? I thought, since the siege was my responsibility, we might send in two members of my staff.

CHATHAM: The Admiral’s going to have to send someone in too, isn’t he?

COOTE: I’m afraid it can’t be helped. He’s chosen Captain Cockburn.

CHATHAM: Well, we can’t let him get one over on us. We need a full colonel.

COOTE: …. but I haven’t got any full colonels on my staff.

CHATHAM: Then we’ll have to send in one of mine. Colonel Long will do.

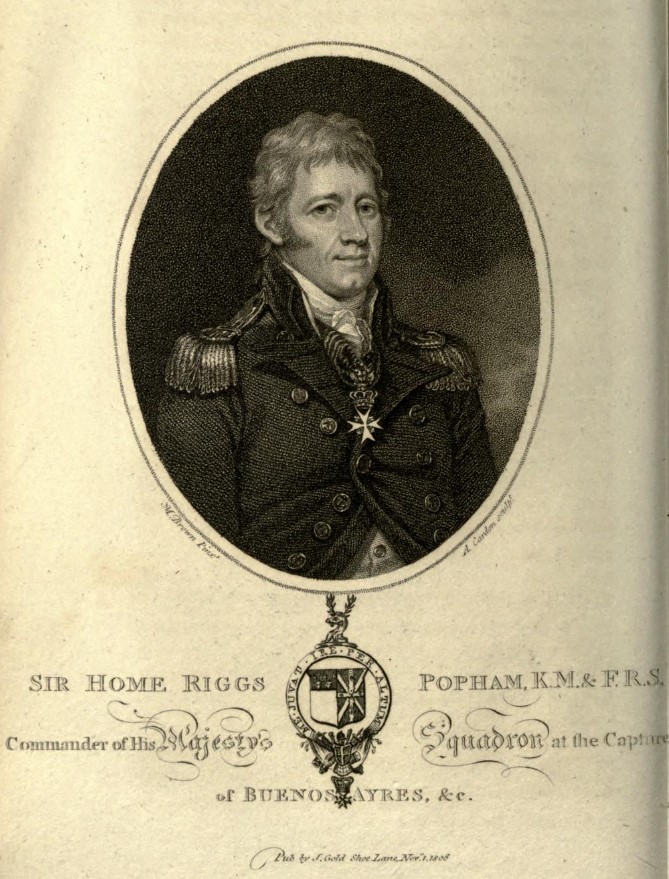

Robert Ballard Long (wikipedia)

COOTE [staring at him]: But … but I was in charge.

CHATHAM: So we’re agreed, I’ll send in Colonel Long.

[Sound of running from a distance; gets closer and closer and closer, until…]

STRACHAN [breathless]: I’M HERE! Did I miss anything?

CHATHAM: Ah, Sir Richard. I trust your boat isn’t too damaged.

STRACHAN: Ship. And I have absolutely no idea what you’re talking about.

CHATHAM: Of course you don’t. [BROWNRIGG looks meaningfully at CHATHAM] [Long pause] [CHATHAM looks like he’s struggling with himself, then says, through gritted teeth] You and your men did a splendid job.

STRACHAN [beaming]: Thanks, Johnboy.

CHATHAM: Now we’ve sent our commissioners, and we wait to find out what terms the French will accept to surrender.

COCKBURN: Admiral. My lord. The city has surrendered. Here are the terms.

CHATHAM: Excellent. The entire garrison is becoming prisoners of war; we can take possession of the city as soon as they have evacuated.

STRACHAN: And then do we press on to Antwerp?

CHATHAM: Have you got my men and ordnance supplies through the Sloe Passage yet?

STRACHAN: …………… Oh goodness, is that the time? I really must be off; appointment in Batz, don’t you know. [Runs off at full speed]

CHATHAM [calling after him]: I suppose not, then.

COOTE: Here are the orders of the day for tomorrow, when the French will march out of Flushing and pile their arms. [pause] After that, my lord … you are going to South Beveland, yes? And on to Antwerp?

South Beveland

CHATHAM: Well, those are my orders.

COOTE [visibly excited now]: Oh, I can’t wait to lay siege to another city!

CHATHAM: You’re not going. You need to stay here and garrison Walcheren.

COOTE: But you said—

CHATHAM: You said you wanted to be in charge here, yes? Well, now’s your chance.

COOTE: If you say so, sir. [whispers as he retreats] Bastard.

STRACHAN [coming back in]: What’s his problem?

CHATHAM: Indigestion. Got your ship off that rock yet?

STRACHAN: You’re never letting me live that down, are you?

CHATHAM: No. So. Are my men through the Sloe?

STRACHAN: Wow. I really keep forgetting these meetings with Sir Home Popham. Really must get a better grip of my schedule. [zips off]

[Next day, outside Flushing]

COOTE: Men! Salute! [Men salute] [COOTE consults watch] Where is he? It’s eight o’clock already.

BROWNRIGG: Did you really expect him to be on time?

COOTE: I mean, the French are over there waiting. It’s getting hot.

BROWNRIGG: You did say seven in the morning, General.

[Men still salute; starting to look a little constipated now]

COOTE: Oh for goodness’ sake, at ease. I don’t think he’s coming any time soon. Are you sure he’s coming at all?

BROWNRIGG: Here he is now.

[CHATHAM and his suite turn up, crisp and fresh. Everyone else glares at them, dripping with sweat.]

CHATHAM: Well, where are the French? What are you waiting for?

COOTE: I can’t imagine.

CHATHAM: Let’s get them marching, then. We haven’t got all day.

[French march out. Rather ragged. They lay their arms at CHATHAM’s feet.]

COOTE: Well, that’s them gone. [hopefully, to CHATHAM] Are you going now, too?

CHATHAM: Yes, as soon as I—

COOTE: I’ve already packed your bags.

CHATHAM:—that’s kind.

COOTE: And loaded them up. In fact, I sent your baggage train out of Middelburg yesterday. It’s waiting for you at Arnemuiden.

CHATHAM: You really shouldn’t have bothered.

COOTE: No, no, I really, really wanted to help. Shall I have your horse saddled?

BROWNRIGG: Lord Chatham! I’m afraid you’ll have to postpone going to South Beveland for a day or so. A letter’s just come from the Treasury. They’re refusing to send us any more money to pay the troops.

[COOTE slopes off, cursing]

CHATHAM: What? Let me see that. [Snatches letter off BROWNRIGG] ‘Dear General Brownrigg, No, you can’t have any more money. We haven’t got any. Take it off the local population—you’ve conquered them, after all, and they should be expecting it. Now get on with it, I feel I’ll have grown a beard before Flushing finally falls. Yours sincerely, Huskisson.’ Argh, the fool! Fetch me my writing desk.

BROWNRIGG: Certainly, sir.

CHATHAM [writes]: ‘Dear Mr Huskisson, the island of Walcheren has surrendered to us, and we really shouldn’t set a bad example by taking all their gold, especially when they have to feed us and keep a roof over our heads. The men haven’t been paid for a week and are starting to get restless. Please send us some money before they mutiny, and furthermore you’re an idiot. Sincerely yours, Chatham.’

BROWNRIGG: Looks fine, sir. Well done.

CHATHAM: Right then, I’m off to South Beveland. Not that we can go far; the ordnance supplies are still stuck in the Sloe. What in the name of all that’s holy is the Admiral doing?

BROWNRIGG: …. I did hear a rumour—

CHATHAM: What?

BROWNRIGG: Nothing of significance. Only … only I heard someone say Strachan had asked Lord Rosslyn if he’d consider sending the troops on South Beveland under his command on to Antwerp…

CHATHAM: WHAT?!

BROWNRIGG: I know, he should have asked you first.

CHATHAM: THIS IS A BLATANT USURPATION OF MY PREROGATIVE AS COMMANDER OF THE FORCES!

BROWNRIGG: Yes, I know, but—

CHATHAM: I SHALL NEVER SPEAK TO THE MAN AGAIN!

BROWNRIGG: You might have to.

CHATHAM: WHY?

BROWNRIGG: Well, you’re engaged in a joint concern with him. He’s also standing right behind you.

STRACHAN: Hey, Johnboy, Sir Home Popham says we probably ought to move it before the 30,000 French reinforcements headed for the Scheldt basin make it here. Could you—

CHATHAM: HANDS OFF MY TROOPS!

STRACHAN: … I haven’t touched them?

CHATHAM: NOBODY IS GOING TO ANTWERP WITHOUT MY SAY-SO. NOT EVEN LORD ROSSLYN’S MEN.

STRACHAN: …. Ah. About that—[CHATHAM brushes past him, almost knocking him over] Bastard.

BROWNRIGG: Well, you did try to go over his head and press on to Antwerp without him. What did you expect?

STRACHAN: We could be here all year if I waited for him.

BROWNRIGG: He’s on his way. How are the transports in the Sloe?

STRACHAN: Dear God, I have another appointment. How do I manage to forget about so many of them? [Disappears]

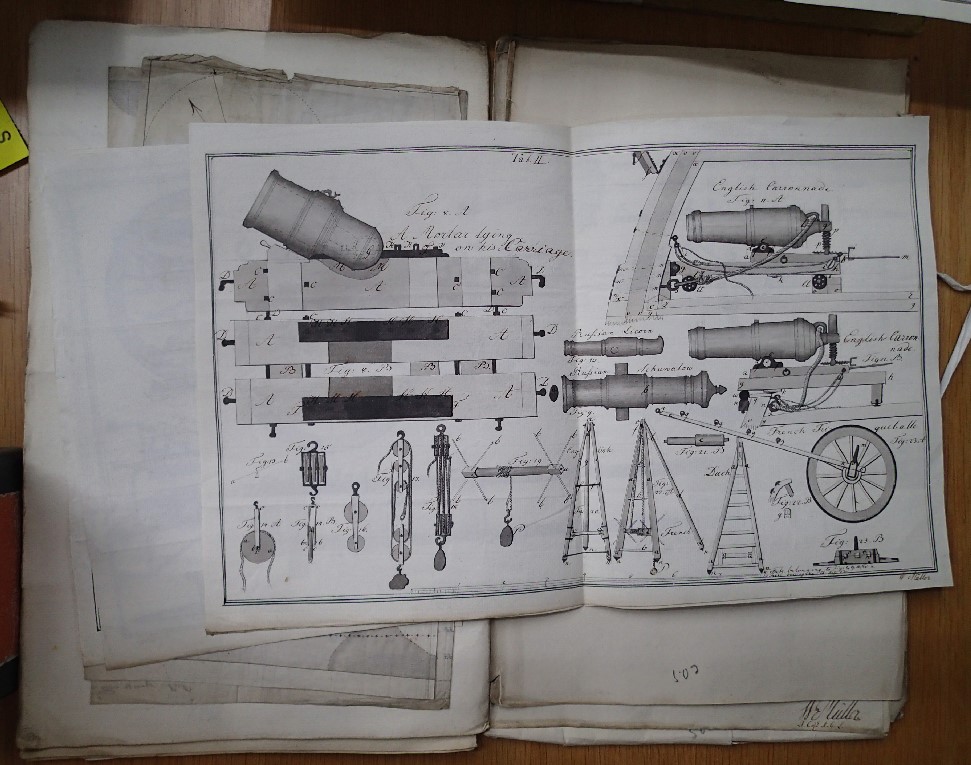

COLONEL LONG: General Brownrigg, we have a problem.

BROWNRIGG: What, another one?

COLONEL LONG: Er, this one’s a biggie. Take a look at these sick returns. [Hands BROWNRIGG a paper]

BROWNRIGG: So what? We always have some sickness on campaigns. This weekly report suggests sickness is a little higher than usual, but nothing we can’t handle.

COLONEL LONG: That’s not a weekly sick return. That’s the sick since yesterday evening.

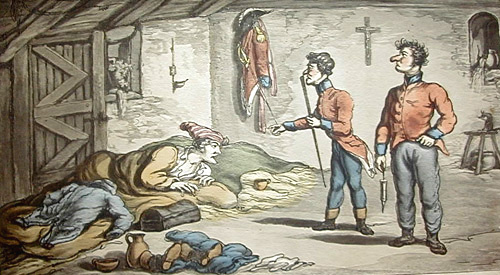

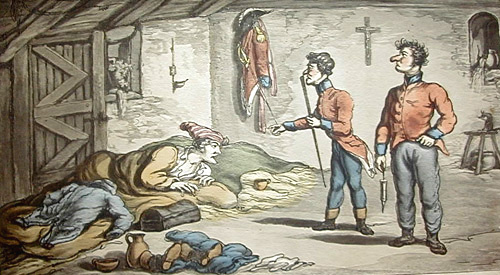

Johnny on the Sick List, Thomas Rowlandson (from here)

BROWNRIGG: Seriously?! [Looks at document] [Stares at it some more] [Long pause] Shit.

COLONEL LONG: That’s the same thing I said.

BROWNRIGG: Keep an eye on it. It may be nothing.

[Next day, on South Beveland]

CHATHAM: Well, this is nice.

BROWNRIGG: Here are Lord Rosslyn and Sir John Hope.

ROSSLYN: Welcome to South Beveland, Lord Chatham. Happy to report absolutely zero chance of our getting to Antwerp now. Thirty thousand Frenchmen between here and the city. To press on would be madness. Plus, we’re starting to get a lot of sick.

CHATHAM: That many? Nobody’s sick on Walcheren.

BROWNRIGG: Um.

CHATHAM: You mean you knew about this? How long has this been going on for?

BROWNRIGG: A few days, I think.

CHATHAM: May I see your sick returns? [ROSSLYN hands them over] These aren’t so bad. I mean, 300 since the beginning of the campaign is—

ROSSLYN: Three hundred today, my lord.

CHATHAM: Today?!

ROSSLYN: Yes. We’ve had pretty much that many sick every day for the last week.

CHATHAM:

BROWNRIGG: Erm. And on Walcheren.

CHATHAM:

STRACHAN [dashing up, breathlessly]: Here I am! I heard you wanted to see me, Rosslyn, old boy? Are we going to Antwerp then? I—hello, what’s he doing here?

CHATHAM: My word, is somebody talking?

STRACHAN: He seems to have gone deaf. JOHNBOY CAN YOU HEAR ME

CHATHAM: I think it may be the wind.

STRACHAN: Must have been the bombardment. Has that effect on some people, loud noises. Bursts their eardrums. I THINK YOU SHOULD HAVE YOUR EARS CLEANED OUT

BROWNRIGG: Strachan, just leave it, he’ll be fine.

ROSSLYN: What is it, Admiral?

STRACHAN: Now he’s here [points at CHATHAM, who flinches], I guess we’re all going up to Antwerp now? Eh? Eh?

BROWNRIGG: And the ordnance supplies in the Sloe?

STRACHAN [proudly]: They’re all here. Look! They arrived this morning. I guess this means we’re ready, yes? [silence] [longer silence] [STRACHAN looks worried] Yes?

BROWNRIGG: Now here’s the thing. You know when we last spoke of taking Antwerp, before Flushing fell?

STRACHAN: Of course.

BROWNRIGG: When there weren’t nearly so many French in the Scheldt basin?

STRACHAN: Yes, but—

BROWNRIGG: Nor was sickness tearing through the army at an alarming rate?

Evacuation of Suid-Beveland, 30 August 1809 (from here)

STRACHAN: I heard rumours about that, but aren’t we—

CHATHAM: NO. No, we bloody well are not.

STRACHAN:

CHATHAM: Our men got stuck in the Sloe and we missed our chance. You bastard.

STRACHAN: Well, if you’d hurried up with the siege of Flushing—

CHATHAM: I bloody well would have done had you got your BLEEDING ships through the BLEEDING Deurloo and into the West Scheldt!

STRACHAN: Well, if Lord BLEEDING Chatham had taken adverse wind into account—

CHATHAM: I DON’T WANT TO HEAR ANY MORE ABOUT WIND!

BROWNRIGG [to ROSSLYN]: I rather preferred it when they weren’t talking.

STRACHAN:—what did you expect us to do, pull the boats down the river on a piece of string?

CHATHAM: I EXPECTED YOU TO GET ME TO SANDVLIET YOU FOOL

STRACHAN: WELL I CAN’T CONTROL THE WEATHER—CAN YOU?

CHATHAM: I’LL SHOW YOU WEATHER IF YOU COME ANY CLOSER

BROWNRIGG [hastily]: My lord, I think you should go and have a rest. Admiral, perhaps … a walk? In the fresh air? [The naval and army commander leave the room; BROWNRIGG looks at ROSSLYN] Jesus Christ.

ROSSLYN: I know. As though sickness wasn’t enough, eh?

[Later]

LONG: General Brownrigg, the latest Gazette has just come in.

BROWNRIGG: Oh splendid. I wonder what—BUGGER

LONG: What is it?

BROWNRIGG: Did you read Strachan’s letter?

LONG [reads]: ‘I wanted to keep going on to Antwerp, but the generals were all against. I had the fleet ready to take us there and the army said no.’ Oh my god.

BROWNRIGG: He’s trying to play the army off against the navy.

LONG: And pin the blame on Lord Chatham.

BROWNRIGG: Has His Lordship seen this?

LONG: Are you going to tell him?

BROWNRIGG: Maybe you should.

LONG: You’re QMG.

BROWNRIGG: You’re Adjutant General. You deal with the correspondence.

LONG: You usually do the letters home, though.

BROWNRIGG: I’m senior to you. I order you to tell him.

LONG: You bastard. [enters CHATHAM’s room] Your Lordship?

CHATHAM [writing; doesn’t look up]: Yes?

LONG: The Gazette has arrived.

CHATHAM: Mmhmm.

LONG: There’s a really nice bit in it reprinting your last dispatch. [pause; really fast] And Sir Richard Strachan’s written a letter blaming the failure of the campaign on the army and exonerating the navy from all responsibility. [more slowly] And some stuff about the fall of Flushing.

CHATHAM: Very good, I—hang on, what?

LONG: It’s not as bad as it sounds—

CHATHAM [reading]): No, it bloody is as bad as it sounds.

LONG: I’m sure he didn’t mean it. The Admiral—

CHATHAM: —is a dead man. BROWNRIGG! [BROWNRIGG hurries in] Have you seen this?

BROWNRIGG: It’s not as bad as it looks, my lord—I’m sure he didn’t mean it—

CHATHAM: Get the Admiral in at once! And get rid of the awful echo here!

BROWNRIGG: I had already thought to summon him, my lord, but nobody can find him. I got a letter from him saying he wasn’t feeling well and had gone off to get some fresh air. I hope he hasn’t got the prevailing fever.

CHATHAM: I really hope he has.

BROWNRIGG: And, er, sir, I—

CHATHAM: What now?

BROWNRIGG: These newspapers came from home too.

[CHATHAM reads in silence] [his face changes]

BROWNRIGG: They’re not very complimentary, are they?

CHATHAM: This one actually calls for my court martial.

BROWNRIGG: I’m sure you’ve had worse.

CHATHAM: This one calls me an indolent, effete idiot unfit for public business.

BROWNRIGG: My goodness, those journalists are scamps.

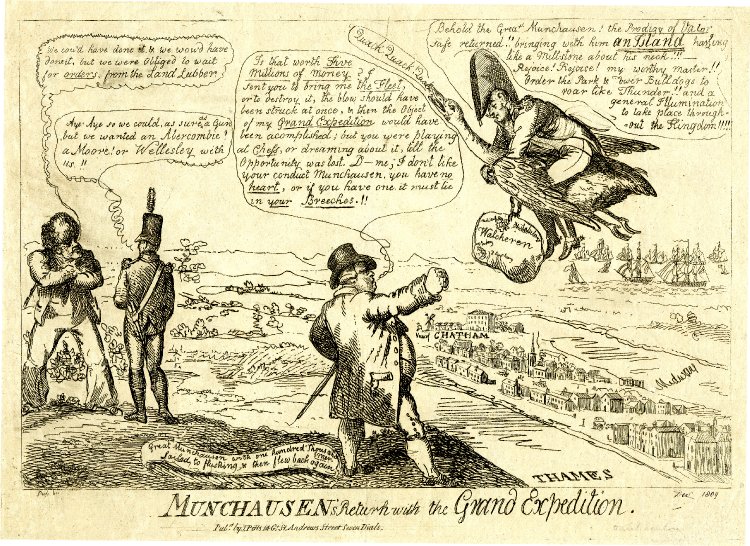

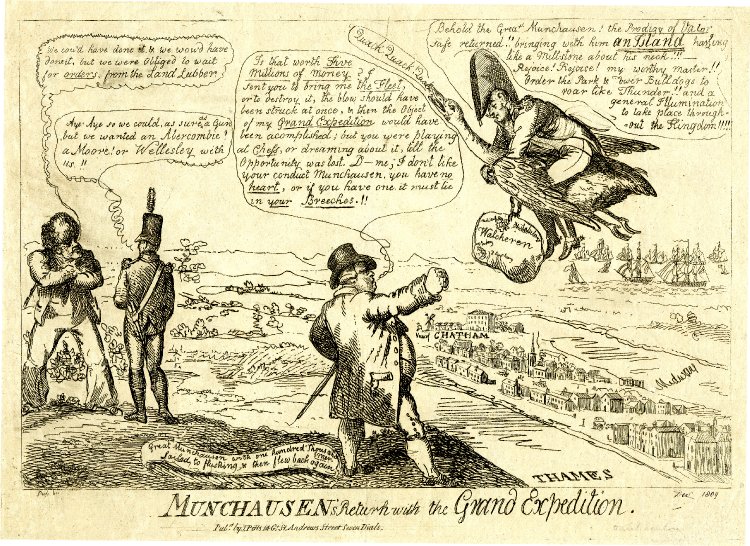

Just one example of a print showing a sailor (far left) complaining Chatham’s army directly caused the failure of the expedition (From here)

CHATHAM: If there’s any more bad news, tell me now, because I think I’m going to burst a blood vessel, so we might as well make my death a clean one.

BROWNRIGG: Well, there is … one thing. Apparently the Duke of Portland’s had a stroke.

CHATHAM: He’s resigned over ill health?

BROWNRIGG: No, he recovered. But then Canning found out the expedition was over and said Portland had promised to fire Castlereagh from the War Department if the campaign failed. Castlereagh found out. They both resigned. There was a duel.

CHATHAM: Please tell me one of them died. No. Better. Please tell me they both died.

BROWNRIGG: Castlereagh shot Canning in the—erm. The thigh?

CHATHAM: Not quite as good as if he’d killed him, but my day is looking up.

BROWNRIGG: Unfortunately they took the government down with them. Portland left office.

CHATHAM: Who replaced him?

BROWNRIGG: Spencer Perceval.

CHATHAM: Bugger. He hates me. [Pause] Please find me the Admiral. I need to shout at someone.

BROWNRIGG: I’m sorry, my lord, I really can’t—

CHATHAM: STRACHAN!

POPHAM [comes in]: I’m afraid he’s not here, my lord. He’s ill.

CHATHAM: How sad. Is it the wrong wind again?

POPHAM: No, he’s just ill.

CHATHAM: Conveniently so. Tell him if he wants a proper illness, I’ll gladly break both his legs for him.

POPHAM: I’ll be sure to pass on the message.

[CHATHAM exits]

STRACHAN [poking head out of a vase]: Is it safe to come out yet?

POPHAM: Soon. He sails tomorrow.

STRACHAN: Good, because it’s a bit cramped in here.

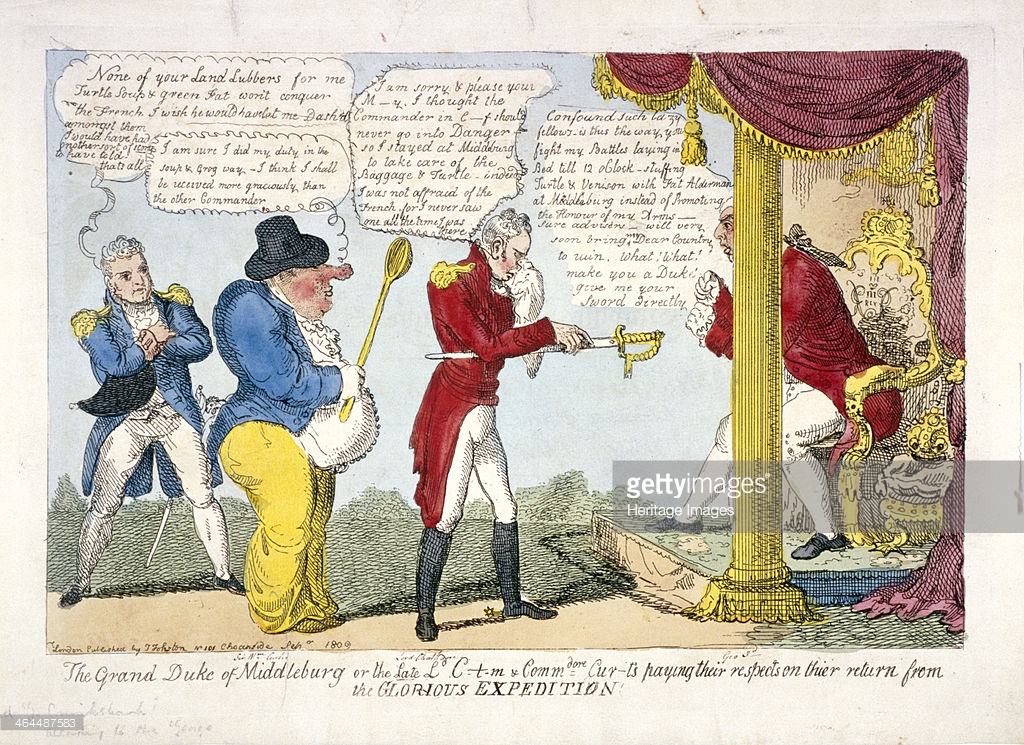

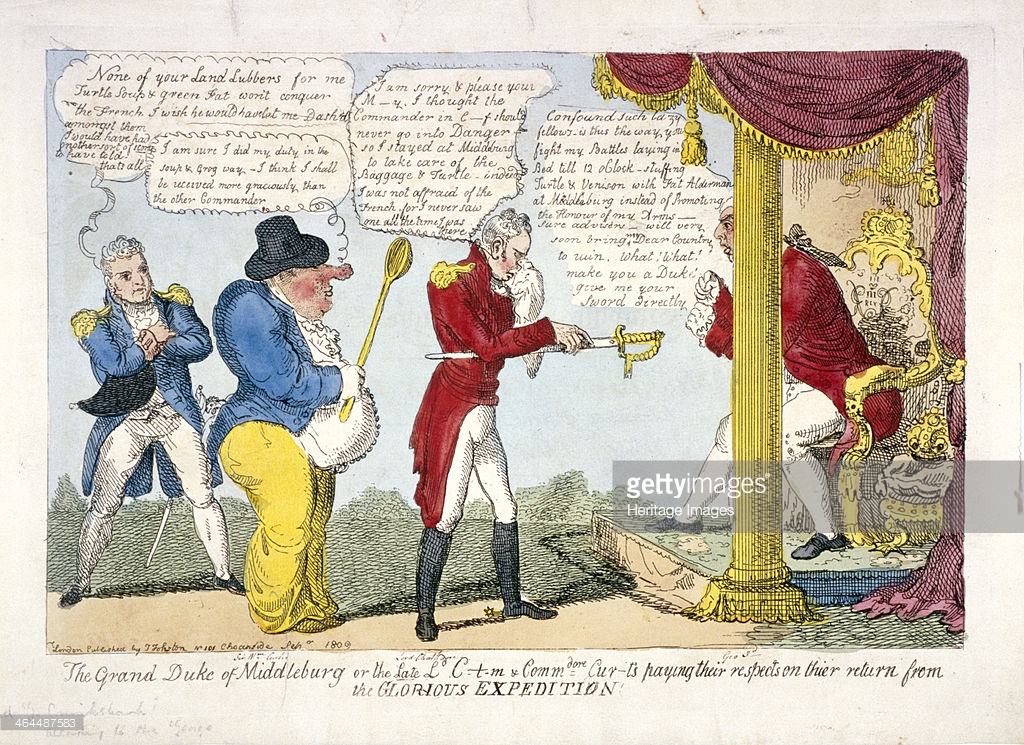

Yet another print showing Strachan (far left) blaming Chatham for the expedition’s failure

[Next day]

CHATHAM: Come Brownrigg, time to say farewell to this place. We have had good times here, have we not? Glory, victory, and memories to last a lifetime. Oh—who’m I kidding? The place is a disease-ridden dunghole. Sir Eyre Coote, have fun without me. [Runs up gangplank and disappears]

COOTE: Thanks for nothing. [Turns back] Now, all we have to do is survive until we get called home, and all will be well.

[Stares at troops. As he watches, several fall down on the spot]

COOTE [brightly]: Here’s the intrepid warrior, facing certain death from disease on a godforsaken island with 16,000 men, half of whom are already ill. What could possibly go wrong?

STRACHAN [distantly, from vase]: Is it safe to come out yet?

![Illustrated Battles of the Nineteenth Century. [By Archibald Forbes, Major Arthur Griffiths, and others.]](https://thelatelord.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/sir_eyre_coote_born_1762.jpg?w=223)