I should be reading about Sir Home Popham right now, and I am. Honestly I am. Well, mostly I am. Because this week I fell down a massive research rabbit-hole and have been mucking happily about at the bottom of it ever since.

It’s the same thing that happened when I felt compelled to spend a fortnight researching the elusive Major Charles James, and in fact the circumstances are similar. James was a shady character whose public persona concealed a whole world of secret activity. My new chap also seems to have led several parallel lives, some of them highly dangerous.

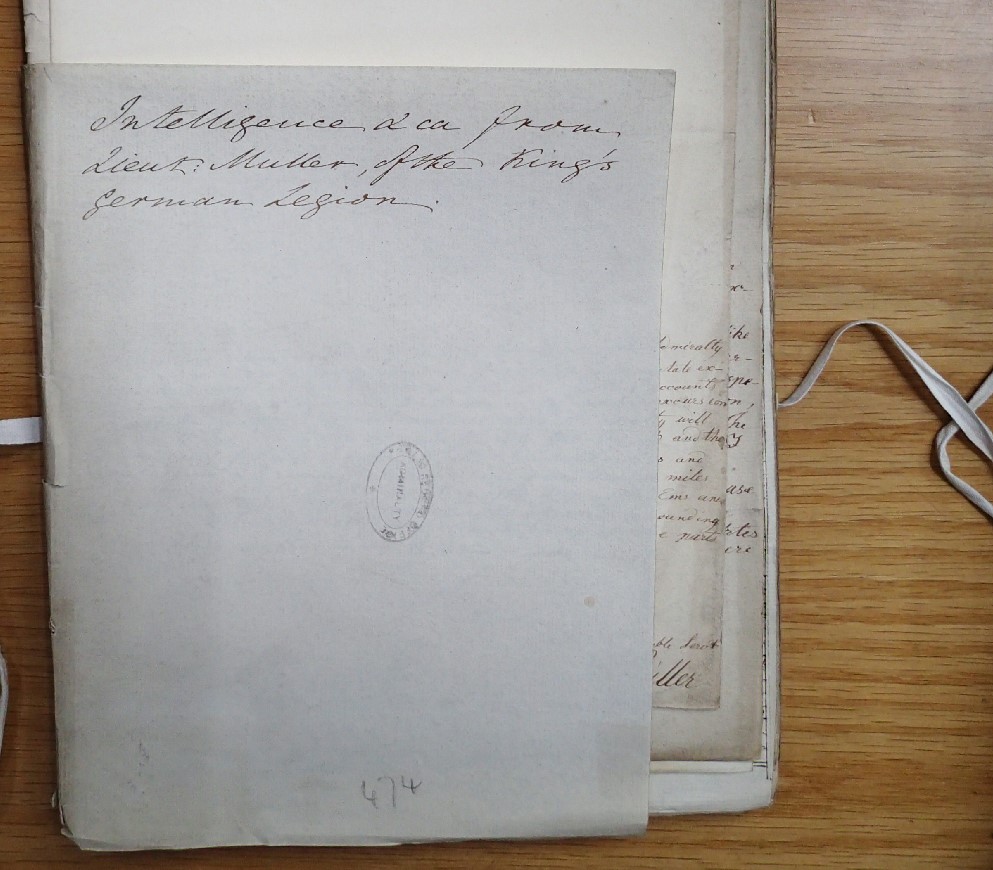

I first encountered this chap while working through The National Archives (TNA) ADM 1/4354, which (rather excitingly) purports to be Secret Correspondence relating to the naval station in the Downs, 1809–10. I was hoping to find some evidence of Sir Home Popham’s activities during the Walcheren campaign: as it happens he was not mentioned once, but I did find a whole ream of correspondence from Lieutenant William Muller, King’s German Legion.

After reading a few pages I realised I had to find out more. And when I started to look, I found stuff. Lots of stuff, in fact, because Lt Muller KGL was a pretty cool guy. So without further ado may I introduce you to Wilhelm Müller, a chap my son has (aptly enough) described as ‘the German James Bond’.

Early life

Wilhelm Müller was born on 13 May 1783 in Stade, Hanover, reasonably close to Hamburg on the River Elbe.[1] His mother was Portuguese; his father, Christian Gottlieb Müller (1753–1814), owned a fleet of merchant vessels and was a Hanoverian customs officer.[2]

Young Wilhelm probably spent some years training to be an engineer before going to study at the University of Gӧttingen in 1803, where he received a PhD and was for some time employed as a Public Lecturer of Military Sciences. (There was a family history of dual military/academic life: Müller’s grandfather had been professor of mathematics at the University of Gießen alongside being chief engineer of the Duchies of Grubenhagen and Cadenberge.[3])

Müller claimed he had taught ‘several Russian, German, and Polish Princes, three of whom hold … the rank of generals in the French and Russian service’. He taught a broad course, liberally founded on mathematics (he was friends with Carl Friedrich Gauß) but also including ‘orthography, geography, general history, the languages … dancing, fencing, riding, and even jumping and swimming’ as well as sciences (‘natural philosophy’) and moral development. He also travelled ‘through France, Prussia, Saxony, Bavaria, Austria, Westphalia, Holland, &c. in order to inspect all remarkable contrivances of machines and inventions, and particularly all military inventions … [and] fields of battle … where the present sovereign of France, and other celebrated warriors, evinced the superiority of their talents over other eminent generals’.[4]

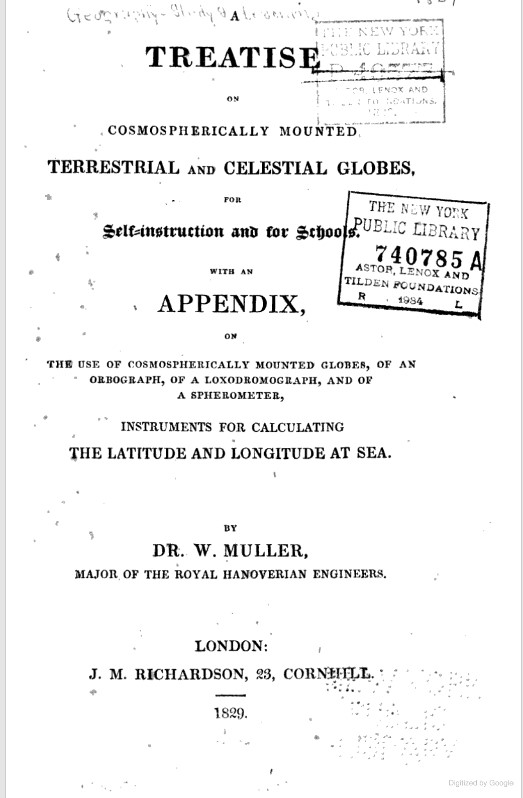

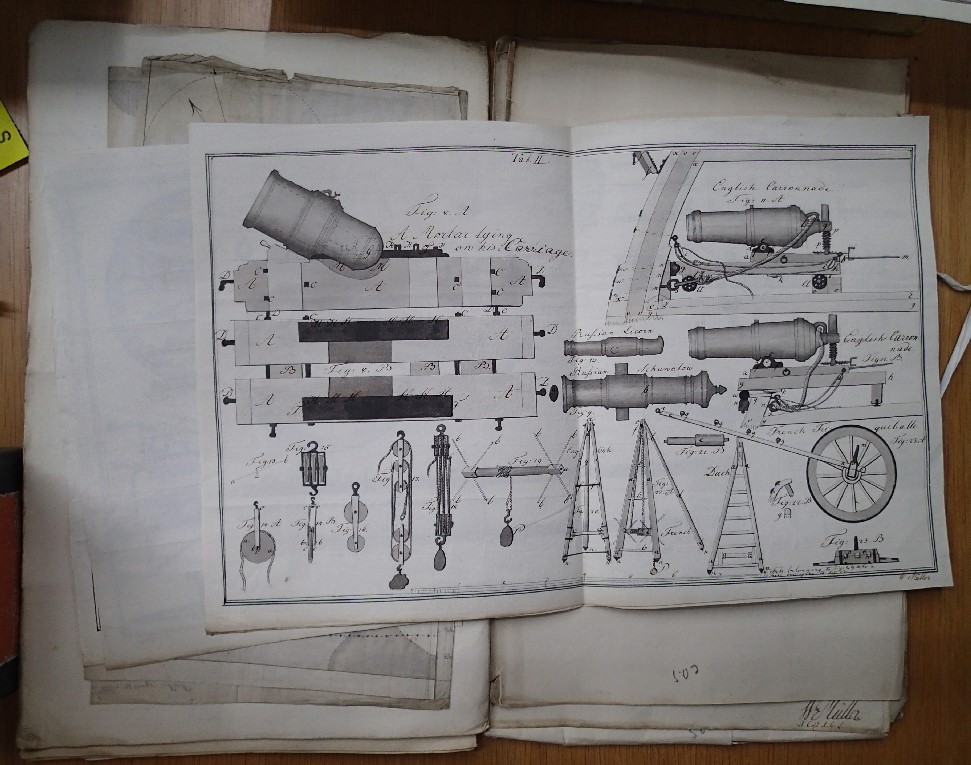

He authored several books: on analytical trigonometry (1807); on the elements of mathematics more generally, including arithmetic, algebra, geometry, stereometry, and spherics (1807); a military encyclopaedia (1808); a handbook of artillery (1810); A Relation of the Operations and Battles of the Austrian and French Armies in the Year 1809 (1810), including details of the Battle of Wagram; Elements of the Science of War (3 vols, 1811); and several books from the 1820s and 1830s on cosmography and terrestrial globes (he later engaged in an extended dispute with Johann Caspar Garthe over a particular kind of globe, which both separately claimed to have invented).[5]

‘The German James Bond’

On 24 April 1809, Dr Müller’s life took a different turn when he was gazetted 2nd Lieutenant in the Engineer’s Corps of the King’s German Legion. What persuaded him to return to military life is unclear, but he was probably already working undercover for the British government. Perhaps the military rank was intended as some sort of protection.

Müller was known to and employed by various government departments. In his letters he namechecked William Huskisson (War Department), Joseph Planta (Foreign Office), William Wellesley Pole, John Barrow, and John Wilson Croker (Secretaries of the Admiralty), and Lord Mulgrave (First Lord of the Admiralty). Clearly a man like Müller, intelligent and fluent in German, French, and likely Dutch (living as close as he did to the Dutch border), was a valuable commodity. By the summer of 1809 he was being employed to scout out French fortifications between Boulogne and Bergen-op-Zoom and to report on affairs in northern Germany. As a trained engineer (and an expert in military fortifications at that), he was the perfect man for the job.

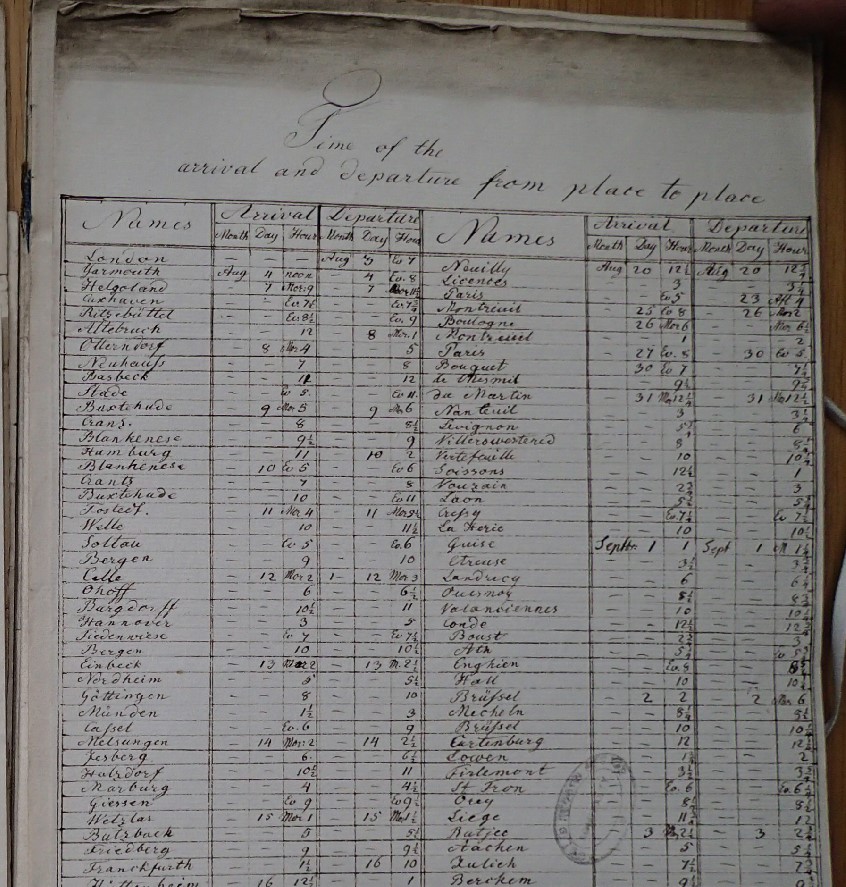

Müller’s exploits – his ‘excursions’, as he called them, rather light-heartedly – are covered at some length (and detail) in TNA ADM 1/4354. These are his reports of two trips, one at the end of June/early July 1809 and one in August and September 1809.

‘Excursion’ 1: 29 June–15 July 1809

Müller was clearly not afraid to strain his faculties and bodily strength to the limit, and his report of his July 1809 trip is particularly dizzying. It began on 29 June, ‘about 3 hours after I had the honor of receiving the necessary papers from your [William Wellesley Pole’s] hands’. By noon on the 30th of June he was on board a cutter, the Princess of Wales, making for Heligoland, where he arrived on 3 July.

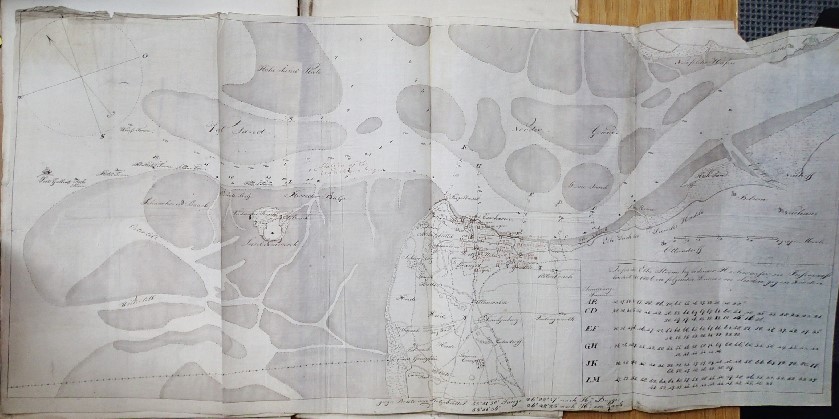

At this point the journey went a little crazy. Müller wrote a letter to the senior naval officer at Heligoland asking him for a cutter to be sent to meet him on the 9th or 10th July at Ems. Having given himself a rendezvous, Müller then landed at Norden at 10 pm on 4 July – presumably to be under cover of darkness – and travelled overnight to Emden, a journey of 19 miles. An hour after arriving at Emden, and around dawn, he was in a boat taking soundings of the harbour and of the Ems river. He then sailed a little upriver to Delfzijl then continued his breakneck journey, pausing only to change horses. He arrived at 4 am on 6 July at Zwolle, having done (roughly) 110 miles in 24 hours (on early 19th century roads!).

The next few days passed in similar fashion, with Müller travelling across parts of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and northern Germany, hardly pausing to do anything but examine the fortifications on his path. His observations, which he recorded in his letter to William Wellesley Pole, were similar for every stop: observations on the fortifications he passed; the size and quality of the garrisons; the number of guns; and whether there were any bodies of troops nearby. He must have done all this on the wing, because he really travelled VERY fast.

Most pertinently for me, on 9 July he travelled to the island of Walcheren, which the British were then preparing to invade. Not that Müller stopped to savour the local sights: he spent a single hour in Middelburg (‘surrounded by a Wall and Ditch’), where he learned there were 14 sail of the line at Flushing and Antwerp and 5 ships of the line on the stocks, along with 8,000 seamen and plenty of shipbuilding materials. By 5 pm he was back on the mainland and by 4 am next day he was in France at Bois-le-Duc.

By this point Müller must have realised he was very close to missing his 10 July appointment with that cutter on the Ems, so he cast a swift eye over the fortresses on the French border then nipped back up to Norden (stopping only to take some more soundings on the Ems ‘as far as a ward for my personal safety would permit’). He reached the rendezvous at 2 am on 11 July. Technically he was late, but the cutter was there anyway. Müller landed at Yarmouth three days later and made his way immediately to London, where he arrived on 15 July at 3 pm, hopefully having had a moment to shave and change his clothes.

As Müller put it, ‘I had no time at all for sleep or refreshment except when in the coach or on bord [sic] Ship.’ No kidding. I hope he didn’t faceplant on the table and start snoring halfway through his report to Pole.

‘Excursion’ 2: 3 August–11 September 1809

‘In respect to my remuneration for my troubles,’ Müller wrote, ‘I left it at their Lordships liberallity [sic] either to remunerate me or to give me any further employ[ment], whereby I might receive a proportionate recompense. Accordingly, the following Month … I was again employed on a secret service,’ this time by Lord Mulgrave himself.

Müller’s remit was to check out the French coast closest to Britain and to work out what might be going on in the hearts and minds of the Dutch and German people. This time, however, he had several close shaves. This was, after all, the beginning of August 1809: the Walcheren expedition was in full swing and the French were decidedly twitchy, and definitely on the lookout for British spies.

Müller took precautions. He had to look, as well as act, the part and bought ‘clothes to dress me according to the fashion of the country’: as he explained later, so as ‘not to raise suspicion respecting my dress.’ He also changed a great deal of money through trusted third parties – money he used to buy a carriage and horse, purchase maps and charts, and occasionally outright bribe people for information.

He left London on the evening of 3 August 1809 and landed at Cuxhaven on the 5th. He travelled immediately to Stade, his hometown, because he needed a passport to go to Hamburg.

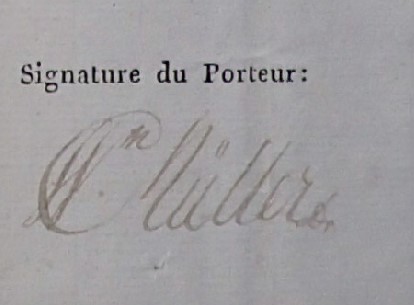

(The passport is a gift to any historian trying to add flesh to a historical personage. The physical description noted that Müller was tall – 180cm, to be precise, or about 5 foot 11 inches – with brown hair and eyes, an oval face with a round chin, and a fresh complexion.)

On 8 August Müller was in Hamburg, where he wrote a letter to William Wellesley Pole recording his initial thoughts about the place and the inclination of the locals (against Bonaparte, he thought). He spent a few days there, buying maps and charts, ‘part of which I thrust [sic, trust] will be usefull, and the rest I was forced to purchase to prevent Suspicion.’

His next major stop was to be Paris, so he needed some people to back him up as a trustworthy man of good character. Accordingly he went to Gӧttingen, where he got the university professors to write him letters of recommendation. On 13 August he was in Cassel, where he found he had company: ‘Jerome Bonaparte was there with almost 2,500 Westphalian troops.’ Apparently Jerome had ordered the execution of 13 ‘estimated Gentlemens [sic]’, which had stirred up anti-French sentiment in the locality.

At Mainz (Mayence) Müller was told he would have to wait two weeks before going into France: ‘however some money procured me directly a French passeport for Paris.’ This wasn’t the last time he used wit and wiles to get his way. At Metz he dined with three imperial messengers, whom he plied with food (and drink). At one in the morning he persuaded one of the couriers, a secretary to Marshal Berthier, to travel with him in his coach (the man was probably too shaky to get back on his horse). His new friend continued to be amazingly talkative. Among other things, Müller learned that Napoleon was keen to finish the war with Austria as soon as possible; that he wanted to invade Russia (this was three years before he actually did, of course); and that the frontiers of France were being strongly reinforced by 18,000 men.

Travelling with the courier may have provided Müller with more than just information: it may also have provided him with immunity. At any rate, they reached Verdun without incident and split up. Müller then went on to Paris, where he arrived at 5 pm on 20 August.

Things now started to get tricky. Müller went to the office of the police and stated his intention to visit Boulogne. He was told, however, that ‘it was forbidden to any stranger to travel to a seaport.’ Müller compromised: he asked for a passport to Montreuil-sur-Mer, still 9 miles or so from the sea. This he secured.

At 4 pm on 23 August Müller left Paris. He arrived at Montreuil the next day at 8 pm. He couldn’t officially go to Boulogne, but that wasn’t going to stop him doing it anyway. At 2 am, therefore, under cover of night, he walked the rest of the way to Boulogne (about 20 miles!). He stayed there long enough to compile some very detailed notes on the defences and garrison and likelihood of a British assault on the place, but then, to his dismay, he bumped into two gendarmes.

Müller must have thought this was the end, but luckily he was able to bluff his way out of this potentially sticky situation by claiming he had lost his way. The gendarmes did not blink at the statement that this man was 20 miles from where his passport said he ought to be and promptly escorted him back to Montreuil.

On 28 August, back in Paris, Müller tried to get a passport for Antwerp. This was wishful thinking – the British expedition to Walcheren was then about 10 miles from Antwerp (it had, however, reached its furthest point and was about to start retreating) – and he failed. Determined to get something out of his visit to Paris, Müller visited an old friend who was a captain in the imperial engineers. ‘By several Means,’ Müller reported with frustrating vagueness, ‘I bought from him for 1800 livres all the maps of French seaports’, along with a map of Westphalia that had been drawn up for Marshal Berthier. While his friend wasn’t looking, he also tore various other charts out of a large book and secreted them in his carriage (I wish he had explained how, but he didn’t, so let your imagination run wild).

With his cabriolet bursting with sensitive documents obtained by the most questionable means, Müller now made his way towards Brussels. On his way he passed several large bodies of troops marching hastily towards the Scheldt and Antwerp, where the British were still expected on an hourly basis. Not unnaturally, Müller ‘hope[d] to meet anywhere … corps of the English Expedition’, but instead ‘I was so unhappy to meet two Gendarmes’ (his phrasing, not mine). Surely he couldn’t be lucky twice? Well actually … he could. They examined his passport and searched his cabriolet: ‘however they saw not my maps etc.’ Müller, presumably sweating profusely, put on the same ‘I am a lost tourist, help help help’ act that had worked so well at Boulogne, and pulled it off a second time. The gendarmes escorted him to Brussels; they left him, and ‘I proceeded discreetly.’ I bet he did.

Flanders, he said, was all in a flap, roused by the proximity of British troops: ‘The general sentiment … was against their Government … they thought likewise that all Holland would soon revolt against their King because a second English Expedition would land in the neighbourhood of Amsterdam.’ (Alas!) At this point, however, Müller just wanted to go home. He therefore made for the Ems as quickly as he could. The moment he got aboard a British ship in the river he showed his ‘official Letter’ from the Admiralty to the commanding officer, who promptly arranged for him to be whisked home by the fastest available route. Müller arrived back in London on 11 September at 9 am.

He was justifiably proud of all he had done: as he wrote to John Wilson Croker, he had travelled 3,592 English miles altogether across his two trips. For this he received a remuneration of £400 (a further £352 was eventually extracted), although Müller did not consider this to cover the risk and discomfort he had undergone.

Later career

Müller may have been engaged in more secret service work in 1813 in the run-up to Leipzig: his record in Beamish’s History of the KGL records that he was employed in North Germany in 1813 and 1814.[7] According to his ODNB entry (and yes, he has one) he did more survey work in Germany and also ‘was employed in the home district’ (i.e. London), so he probably did not serve actively with his regiment abroad.[7] He continued in the KGL, however, and was promoted second captain in December 1812. Here he stuck until the regiment was disbanded in February 1816 and he went on half-pay, although he subsequently served in the Hanoverian army’s engineer corps and was eventually promoted to major. He also became Librarian to the Duke of Cambridge, Governor of Hanover, a position he kept until 1834, and was appointed a Knight of the Guelphic Order in 1821 – perhaps a reward for some of his services?

Private life

After all this, what about Müller’s private life? I wasn’t able to glean much about him as a person from his letters, other than that he seems to have been resourceful, proactive, and quick-thinking, not to mention capable of superhuman abilities to stave off sleep. One thing is for sure: he was not married in 1809, which was possibly one reason why he was willing to undertake such dangerous missions. Müller did, however, latermarry a girl from Newtown in Ireland named Clarinda Catherine Ready, about eight years his junior. Their first child, Wilhelm Adolf, was born in September 1812. Over the next 12 years they had at least five sons (there is no sign of daughters). All the children were born in Stade, which suggests Müller settled back there to bring up his family.

Unfortunately, Müller’s story does not have a tremendously happy ending. He and his wife died within a couple of months of each other in 1846, aged 63 and 55. Their children were not especially long-lived: of the three whose lives I’ve managed to track, Hermann Wilhelm died aged 50, Wilhelm Adolf (the eldest) died aged 46, and David Miles Wilhelm died aged 24.[8]

But what a story their father must have had to tell.

References

All quotations from Wilhelm Müller’s correspondence come from TNA ADM 1/4354.

Many thanks to Lynn Bryant (ever my partner in crime), Rob Griffith, and Gareth Glover for help and pointers.

[1] Date of birth from Werner Kummer, ‘J.A. Brandegger, F. Schneider, J.C. Dibold, J.C. Garthe and W. Müller: minor German globe makers in the late 18th and early 19th centuries’, Globe Studies 51/52 (2005[for 2003/04]), pp. 59–71, p. 68 n 18

[2] His father was an interesting character in his own right. Also educated at Gӧttingen, he was briefly in the British Royal Navy but was invalided out after his leg was permanently damaged during a skirmish with Chinese pirates. He subsequently became captain of a customs frigate on the Elbe and published several works on maritime engineering. See https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_Gottlieb_Daniel_M%C3%BCller (accessed 16 October 2020)

[3] http://m.genealogias.info/mobi/1/upload/moller.pdf (accessed 16 October 2020)

[4] William Müller, Elements of the Science of War, vol. 1, pp. ix-xvi

[5] Kummer, ‘Minor German globe makers’, p. 68

[6] North Ludlow Beamish, History of the King’s German Legion (T&W Bone, 1837), p. 531

[7] H.M. Chichester, revised by James Falkner, ‘Müller, William (d. 1846)’, ODNB online, published 22 September 2005, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/19515, accessed 15 October 2020

[8] These last two paragraphs have been pieced together through searches on ancestry.co.uk.

![Illustrated Battles of the Nineteenth Century. [By Archibald Forbes, Major Arthur Griffiths, and others.]](https://alwayswantedtobeareiter.files.wordpress.com/2019/11/sir_eyre_coote_born_1762.jpg?w=223)

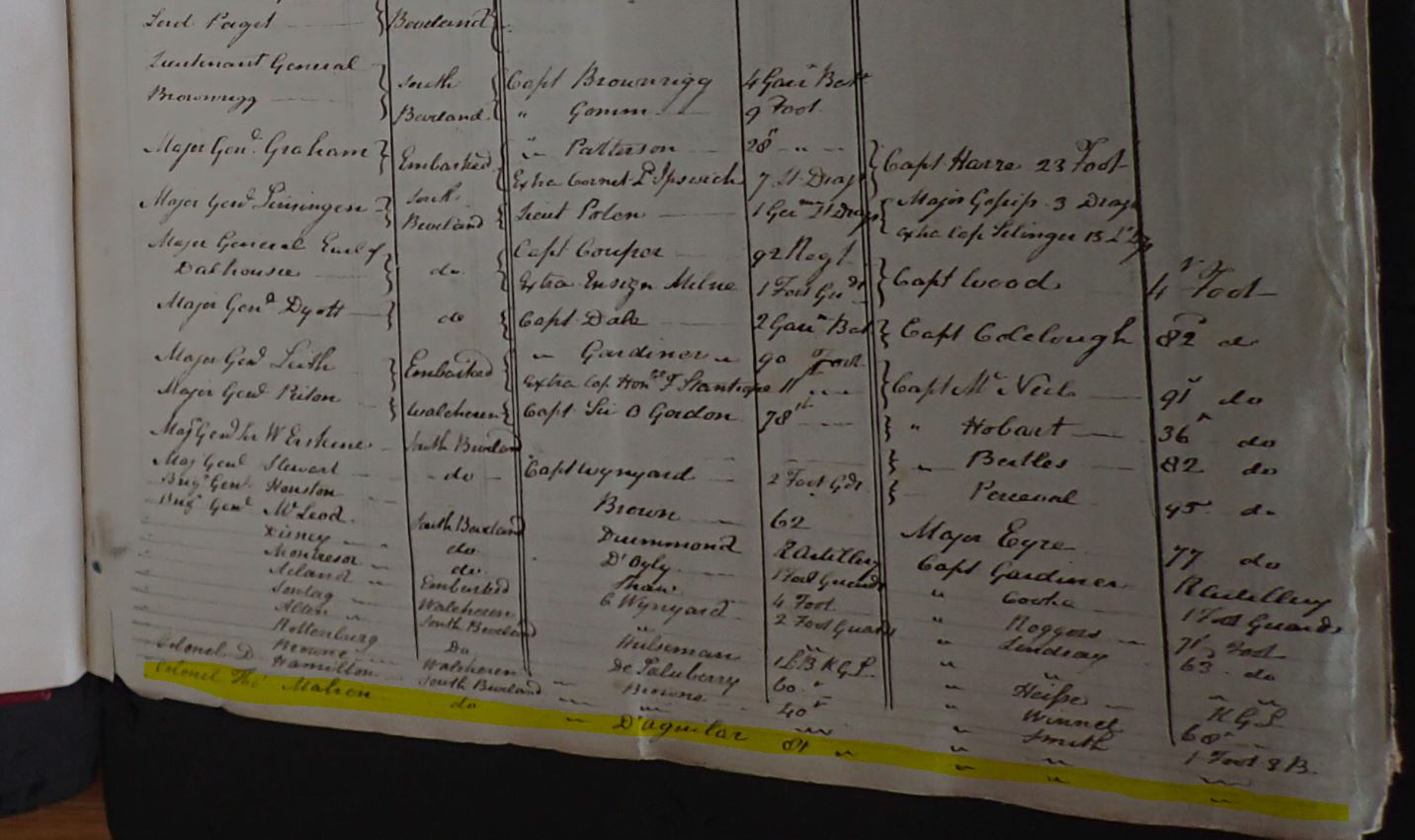

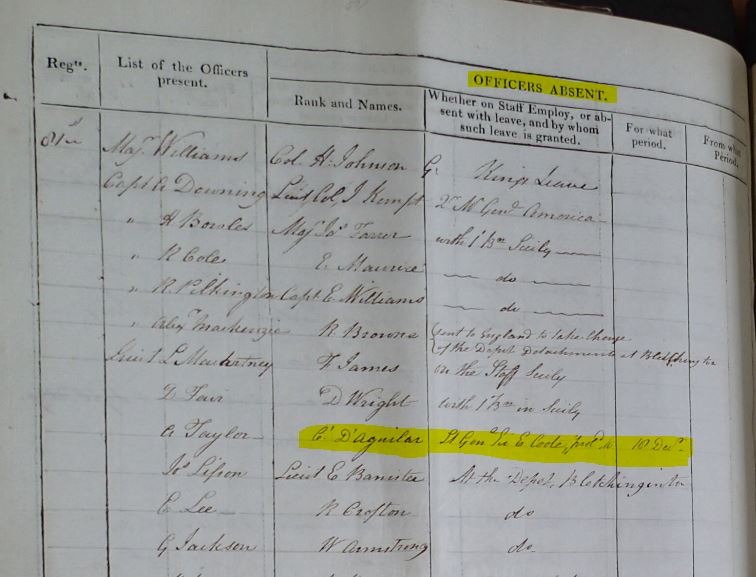

I must admit that D’Aguilar’s authorship is a speculative, rather than a definite, identification. I can’t find any obvious connection between D’Aguilar and the printer of Letters, Richard Phillips, except that Phillips was a well-known publisher of other military works. Nor can I confirm that D’Aguilar stayed at Bedford Square, where the Advertisement at the beginning of Letters is signed. D’Aguilar did, however, go on to publish several other works in his lifetime, including The Officers; Manual (a translation of the Military Maxims of Napoleon).[5]

I must admit that D’Aguilar’s authorship is a speculative, rather than a definite, identification. I can’t find any obvious connection between D’Aguilar and the printer of Letters, Richard Phillips, except that Phillips was a well-known publisher of other military works. Nor can I confirm that D’Aguilar stayed at Bedford Square, where the Advertisement at the beginning of Letters is signed. D’Aguilar did, however, go on to publish several other works in his lifetime, including The Officers; Manual (a translation of the Military Maxims of Napoleon).[5]

The belatedly-published memorandum quoted two naval officers, Sir Home Popham (one of the planners of the expedition) and Captain Robert Plampin, both saying they had both been to Antwerp in the 1790s and thought there would be no problem in landing a large body of men between Lillo and Sandvliet. On that basis, the Opinion made the following statement:

The belatedly-published memorandum quoted two naval officers, Sir Home Popham (one of the planners of the expedition) and Captain Robert Plampin, both saying they had both been to Antwerp in the 1790s and thought there would be no problem in landing a large body of men between Lillo and Sandvliet. On that basis, the Opinion made the following statement: