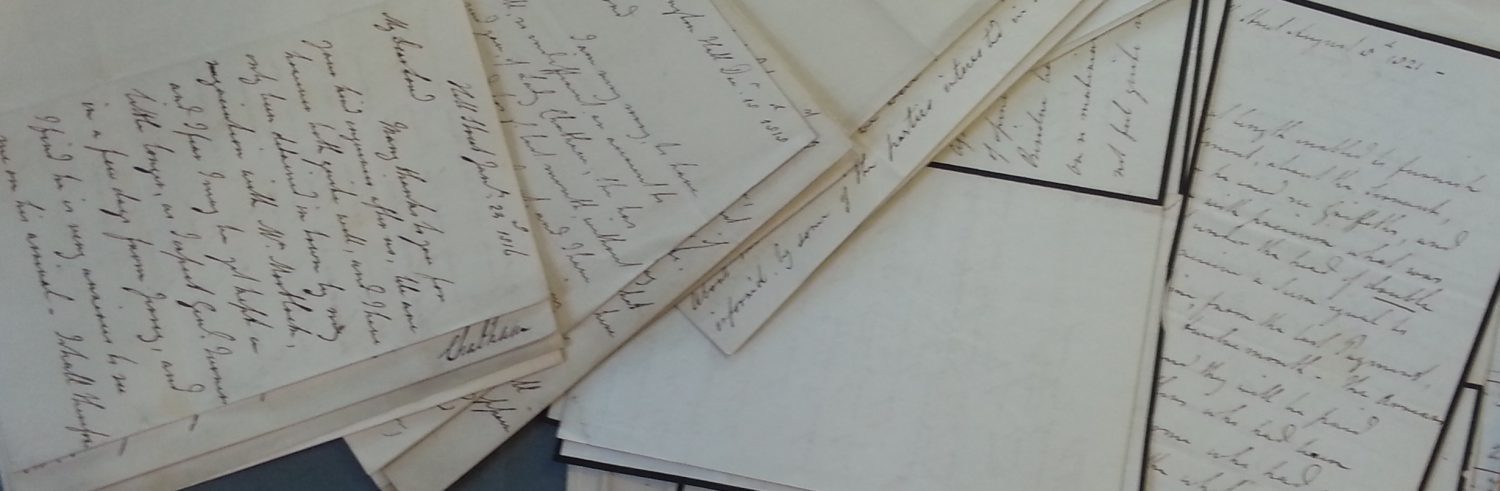

In May 1808 John, 2nd Earl of Chatham braced himself to write to his mother’s old companion, Catherine Stapleton. Mrs Stapleton (the “Mrs” was a courtesy title only, since she never married) had lived more or less permanently with the Dowager Countess of Chatham from 1782 until Lady Chatham’s death in 1803. She thus had a strong claim on John’s remembrances, although I have a feeling she never forgave him for selling Burton Pynsent in 1805.

By 1808, though, Mrs Stapleton was low on funds. I can only imagine sheer desperation drove her to request assistance from John, whom she must have known was not in a position to offer much assistance. He wrote back after a week or so with a draft of money for £150, the best he could do given his bank account was “strictly appropriated, in order to get rid gradually of some incumbrances, which ye misfortunes of late years have brought, to press very heavily upon me.”

Most of these “misfortunes” were clear enough. Many of them were self-inflicted, and for more see my post on the subject of John’s finances generally. I suspect, although I have not yet been able to substantiate this, that John had been sued over the sale of Burton Pynsent by the purchaser of the estate, John Pinney, and the fallout of this was no doubt one minor “misfortune” . The more significant ones were, most obviously, the death of John’s brother William Pitt in January 1806 and the subsequent break-up of his ministry, during which John Chatham lost the salary he had received as a Cabinet member in continuous service since July 1788. In May 1808 he was back in office, but presumably his credit had not yet recovered from eighteen months without a salary.

But there was one other misfortune of note, and John touched on it towards the end of his letter. “Lady Chatham is I hope essentially better, but far from well yet,” he wrote. “This has been a year of sad distress, and confinement to me, but upon the whole I am well” .[1] In November 1808, after another lengthy spate of correspondence (again on financial difficulties), John closed a letter to his banker Thomas Coutts by revealing his wife was still extremely unwell: “I have not seen Lady Chatham for some time, but form her letters I hope she is rather better than she was, tho’ her amendment, I am sorry to say, has been very slow.”[2]

Readers of this blog may recall my discovery, in April last year, that John’s wife Mary suffered from a severe mental illness towards the end of her life. Whether her illness was caused by schizophrenia or something metabolic I am not qualified to say, but it turns out her troubles from 1818 onwards were not unique. Mrs Tomline’s lengthy, somewhat voyeuristic letter to Sir Henry Halford describing Mary’s 1819 condition made a passing reference to a previous attack: “[I] reminded her [Lady Chatham] she had recovered from a former illness … and expressed perfect confidence that she would again recover.”[3] Sir Henry Halford himself recorded, in his diary kept during the period of his attendance on mad King George III, the King early on expressing confidence in Halford’s skill, for he had “saved Lady Chatham from being delivered over to the Mad Doctors.”[4]

A little digging revealed that Mary Chatham had, in fact, been ill for over a year by the time John wrote to Mrs Stapleton. She may in fact not have recovered from the “delirious Fever” that nearly prevented John attending his own brother’s funeral in February 1806, and which marks the beginning of the mental troubles that would plague her on and off for the rest of her life.[5] Certainly she was not well in April 1807, as is made clear in a letter, almost certainly written by her sister Georgiana, in the Leicester and Rutland Record Office Halford MSS.[6]

Georgiana Townshend was Mary’s only older sibling, born in 1761. She was unmarried, and seems to have spent much time as a live-in nurse to Mary during her lengthy periods of ill health, starting with Mary’s rheumatic episode in 1784. Her anonymous letter to Halford (then plain Henry Vaughan) of 14 April 1807 is especially interesting because it corroborates so many of the symptoms Mary suffered from during her relapse ten years later: this was clearly an attack of the same illness, whatever it was.

The letter, obviously written in distress by a woman at the end of her tether, makes difficult reading. As happened in 1818, Mary seems to have struck out, often literally, at those who were closest to her. Georgiana recorded Mary’s use of “violence” towards her sister and mother, as well as her use of “horrid language”, to the extent that the Dowager Lady Sydney had “really become quite afraid” of her own daughter. Georgiana did not, however, think her mother fully understood the severity of the situation. Lady Sydney kept waiting for Mary to snap out of it: “If she (my poor Sister is a little chearfull) her real illness is forgot, & ‘she can be well when she pleases’. Will any body of common Sense think she would not then always be so?”

Mary was clearly all too aware of her own condition, and that Georgiana was reporting everything to Halford. “I hope you never talk of my mind,” Georgiana quoted to Halford from Mary’s latest letter, adding, “that last word was hardly intelligible” . Mary knew she was caught up in a spiral of depression, but could see no way back out to the light, trapped as she was on a circular, claustrophobic path: “[She] has no better opinion of herself … saying she still lived too shut up a life feeling unfit for every thing & making herself more unfit by doing so” . Mary’s inability to break away from the blackness made her moods worse. Georgiana quoted another letter that was little more than a desperate cry for a help Mary knew did not exist:

My cold is better but I am shocking horrible in mind & spirits &c. Oh why, why write to write this so, keep it to yourself … or rather burn it, tell me I may be suddenly different. Nonsense my head can not go on so. God bless you.

She displayed suicidal tendencies, as she was to do ten years later, although Georgiana seemed to think there was no real danger. Georgiana reported her muttering “she could not live in this way (that you perceive is the old Story) [and] she must put an end to it” .

Mary was of course a married woman, and in every marriage there are two people. John had promised to support his wife in sickness and in health, but he cannot have known when he did so just how much sickness there would be in Mary’s life. He and Mary had always been a close couple. Her illness, and its nature, appears to have knocked him completely sideways. He dealt with it in much the same way as he dealt with most of the major problems in his life: by pretending it did not exist. Georgiana referred to John’s wrapping himself up in his armour of denial:

She will not think he thinks her well, tho’ she tells my mother nobody thinks her well, but him. … She has regretted to me that poor L[or]d C[hatham] thought her getting better when she was as ill as ever, & alas! there is I fear too much truth in that.

John’s stiff-upper-lip attitude may have helped him get by on the surface, but unfortunately it was exactly the worst thing possible for Mary. Inevitably their close marriage, subjected to almost unbearable pressure, began to crack. Georgiana’s letter gives an interesting, poignant vignette into the impact of Mary’s illness on her domestic arrangements. Either by medical advice, or because John, too, was not immune from Mary’s violent fits, they were living in different apartments for the first time in their marriage. “I am certain their being on separate floors must keep up the irritation,” Georgiana noted, “but that no-one can help, but she never can have confidence in his thinking her better, while she does not live as usual.”

If only John could wake up, smell the coffee and see what impact his attitude had, but Georgiana suspected it was impossible. The self-replicating nature of the issue distressed her: “She [Mary] cannot get back to where she was with him, & a most unhappy being she certainly is.”

Mary’s sense of entrapment must have been massively increased by her status as a cabinet minister’s wife. John had joined the Duke of Portland’s cabinet as Master General of the Ordnance and, as such, required to attend Court functions, hold dinners, and appear in public on a regular basis. It is clear from Georgiana’s letters that he expected Mary to appear with him, if only to keep up appearances of normality: the scandal, if news of her condition leaked out, would be great. “I dread her making her case more known,” Georgiana fretted to Halford. “… All her servants see it, & I live in dread of a scene.”

The attempts to keep Mary propped up and looking normal are horrifying to read. Georgiana described the hell in which Mary existed, as a public figure required to perform a social role. She quoted a letter from Mary’s maid:

I leave you to judge in what state she [Mary] must have been, before she would attempt to Strike me, which her L[ad]yship actually did on Tuesday at dressing time, fear made me shrink from her, & she immediately became conscious of what she had done, & kept on mumbling to herself … She was very bad in the afternoon, but much worse at dressing time, she never struck me before, but has many times gone off in a very violent way. I asked her L[ad]yship to take some Cordial, which she did[,] afterwards finished dressing, & went out very quietly with my L[or]d. … Since Tuesday her L[ad]yship has been upon the whole tolerably quiet, she complains of being very much tired in the Morning. Her L[ad]yship does not go to bed till after two in ye Morn[in]g.

As Georgiana noted, “She will be relieved by there being no Drawing Room Thursday.” Mary’s existence, drifting in a drug-induced fog from function to function, must have been unimaginable.

Nor was it enough to prevent gossip. By the end of the year Mary’s state was, unfortunately, the stuff of opposition tittle-tattle. “Lady Chatham is at Frognall … under some symptoms of a mental derangement,” Lord Auckland reported to Lord Grenville in November 1807, and in January 1808 Thomas Grenville wrote that Mary was “much disordered in her senses.”[7] These were family connections — the Grenvilles were John’s first cousins — but they were not friendly either to John or the ministry he represented. I find it hard to believe that Mary’s condition was not more widely known.

Mary’s 1807-8 illness may have had a long-term significance. I suspect very much it was a strong reason for Chatham pulling himself out of the running as a potential First Lord of the Treasury following the collapse of the Ministry of All the Talents and the Duke of Portland’s growing ill health. I suspect, too, it was one of the primary reasons why Chatham declined the command of the British Army in the Peninsula. Mary Chatham’s mental problems cast a long shadow. On the one hand they ensured that Arthur Wellesley was appointed in the Peninsula, a major step on the road to victory over Napoleon; but on the other they set John Chatham on his path to Walcheren, and disgrace.

______________

References

[1] Lord Chatham to Mrs Stapleton, 11 May 1808, National Army Museum Stapleton Cotton (Combermere) MSS 9506-61-3

[2] Lord Chatham to Thomas Coutts, 23 November 1808, Kent RO Pitt MSS U1590/S5/C42. I am grateful to Stephenie Woolterton for alerting me to this letter, and transcribing it for me.

[3] Elizabeth Tomline to Sir Henry Halford, undated but September 1819, Ipswich RO Pretyman MSS HA 119/562/716

[4] Sir Henry Halford’s diary [1831-2], Leicester and Rutland RO Halford MSS DG24/941 f 56

[5] Bishop of Lincoln to his wife, 31 January 1806, Ipswich RO Pretyman MSS HA 119/T99/26

[6] All quotations over the next few paragraphs come from [Georgiana Townshend] to Henry Vaughan [later Sir Henry Halford], 14 April 1807, Leicester and Rutland RO DG24/819/1; and [Georgiana Townshend] to Henry Vaughan [later Sir Henry Halford], 14 April 1807, Leicester and Rutland RO DG24/819/2

[7] Lord Auckland to Lord Grenville, 6 November 1807; Thomas Grenville to Lord Grenville, 9 January 1808, Manuscripts of J.B. Fortescue IX, 142, 171

![William Pitt the Elder, 1st Earl of Chatham by William Hoare (Wikimedia Commons) [b]](https://thelatelord.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/471px-williampitttheelder.jpg?w=236&h=300)

![Charles, 4th Duke of Rutland (Wikimedia Commons) [a]](https://thelatelord.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/4th_duke_of_rutland.jpg?w=236&h=300)

![William Pitt the Elder, 1st Earl of Chatham by William Hoare (Wikimedia Commons) [b]](https://thelatelord.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/471px-williampitttheelder.jpg?w=235&h=300)