Home » Posts tagged 'earl of chatham' (Page 4)

Tag Archives: earl of chatham

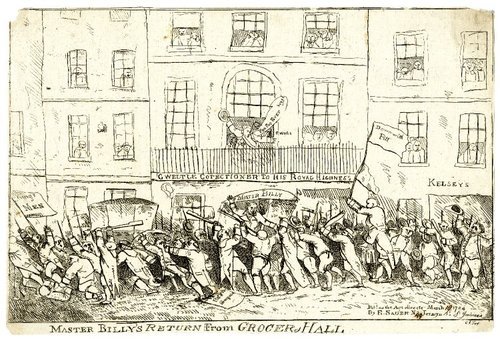

“Master Billy’s return from Grocer’s Hall”

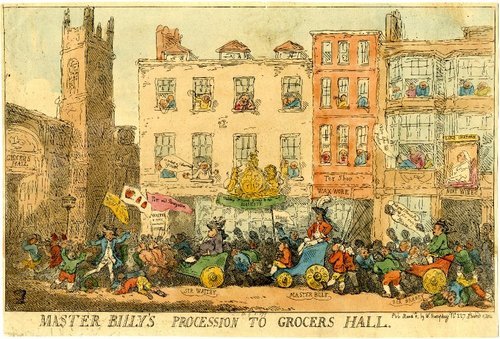

(“Master Billy’s procession to Grocer’s Hall” by Thomas Rowlandson, from here)

It has just been brought to my attention that I missed an anniversary yesterday (28 February). On 28 February 1784, William Pitt the Younger received the Freedom of the City of London at a banquet held at Grocer’s Hall. This was towards the end of the so-called “constitutional crisis” triggered by George III’s dismissal of the Portland ministry and appointment of 24-year-old Pitt at the head of a minority government. Assisted by a combination of behind-the-scenes bribery, eloquence in Parliament, his reputation for purity, and downright luck, Pitt had been slowly gathering public support and chipping away the opposition’s majority throughout February. The Freedom of the City was a great coup for him, since the City traditionally held itself independent of the monarch and had a great deal of political influence. Pitt’s carriage was drawn from Berkeley Square, where he was living with his brother, to Grocer’s Hall by his supporters.

(“Master Billy’s return from Grocer’s Hall”, anonymous, from here)

The way home was, unfortunately, not quite so uneventful. Once again Pitt was drawn through the streets “by a great concourse of people, many of the better sort … as well as by a considerable Mob” (in the words of Pitt’s brother Lord Chatham, who, along with Pitt’s brother-in-law Lord Mahon, later 3rd Earl Stanhope, was also in the carriage). Chatham later set down his recollections of what happened next for Pitt’s biographer, the Bishop of Lincoln, in 1821 (this can be found at Ipswich Record Office, Pretyman MSS HA119/562/688). Chatham wrote:

The Populace insisted on taking off the Horses and drawing the Coach. A Mob is never very discreet, and unfortunately they stopped opposite Carlton House and begun [sic] hissing, and it was with some difficulty we forced them to go on. As we proceeded up St James’s Street, there was a great Cry, and an attempt made to turn the Carriage up St James’s Place to Mr Fox’s house (he then lived at Ld Northingtons) in order to break his windows and force him to light, but which we at last succeeded in preventing their doing.

I have often thought this was a trap laid for us, for had we got up, there, into a Cul de Sac, Mr Pitts situation would have been critical indeed. This attempt brought us rather nearer in contact with Brooks, and the moment we got opposite (the Mob calling for lights) a sudden and desperate attack was made upon the Carriage in which, were Mr Pitt, Lord M[ahon] and myself, by a body of Chairmen armed with bludgeons, broken Chair Poles &c (many of the waiters, and several of the Gentlemen among them).

They succeeded in making their way to the Carriage, and forced open the door. Several desperate blows were aimed at Mr Pitt, and I recollect endeavouring to cover him, as well as I cou’d, in his getting out of the Carriage. Fortunately however, by the exertions of those who remained with us, and by ye timely assistance of a Party of Chairmen and many Gentlemen from Whites, who saw his danger, we were extricated, from a most unpleasant situation, and with considerable difficulty, got into some of the adjacent houses, without material injury, and from there to Whites. The Coachman, and the Servants were much bruised, and the Carriage nearly demolished.

I do not recollect having particularly seen Genl Fitzpatrick, but I distinguished Mr Hare, and the present Lord Crewe extremely active, and I think Lord Robert Spencer, standing at the Door. I remember when the Streets were a little clear, I walked over, with Mr McDowall to Brooks, and went up into ye Club Room, but the Party were either gone home, or gone to Supper.

The next morning I met Lord Ossory in St James’s Street, who attempted to make apologies for what had passed, and to lay it upon ye violence of the Chairmen, some of the Chairs having been broken by the Mob.

I never went to Brooks any more, and I was never able to ascertain further what passed or what first led to the Outrage that night.

Fair enough, I guess!

Oh dear John, part the zillionth

“There is to be a meeting at my house tomorrow Evening at 9 OClock precisely, and I hope your Lordship will be able to attend it”

(Spencer Perceval to John, Earl of Chatham, undated [January 1810], PRO 30/8/368 f 137)

From the emphasis on “precisely” I draw further confirmation that John’s reputation as the “Late” Lord Chatham was not entirely undeserved. 😉

Eleanor Eden by John Hoppner (ca 1800)

And of course the lady most famous for nearly-but-not-quite becoming Mrs William Pitt the Younger.

Interestingly Pitt’s brother John, Earl of Chatham was totally dismissive of the frenzied rumours surrounding his brother’s courtship of Miss Eden in December 1796: “I can not conceive what cou’d induce Bathurst, to write you word, seriously, that my Brother was to marry Miss Eden. I do not believe a word of it, tho he has certainly often been there this year, but I rather fancy the inducement was to talk over the finances with my Lord. Mrs Bankes, who is intimate with the Aucklands assures me there is nothing at all in it, and that Lady Auckland [Eleanor’s mother] amuses herself very much with the report (which is very current) and at the alarm it gives certain Persons, who are afraid, they will not engross the whole of his time as they have been in the habit of doing” (Chatham to Lord Camden, 23 December 1796, Kent RO U840/C254/6)

Perhaps a little bitchy (and one must remember John was not on the best of terms with his brother in December 1796), but interesting nonetheless. I daresay John was one of the least surprised people in England when Pitt decided not to marry Eleanor Eden after all just a month later.

Was John, 2nd Earl of Chatham a waste of space? (Part One)

Now, before you all jump up and shout “Yes! Next question!”, bear with me.

My friends and acquaintances will all know that I have a “Thing” (yes, with a capital T) about John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham. This “Thing” has grown and developed over the years since I found myself, somewhat to my own surprise, writing a novel about him.

Perhaps I shouldn’t need to justify my choice of him as a subject, but sometimes I feel that I do. A few months ago I bought a letter off an antiques dealer written by John in 1802. I took it to an art shop to frame. “Very nice,” the man said as he measured it up for me. “But this Earl of Chatham…. what did he do?” This is a question I get asked a lot….

I think I mentioned before that Sir Tresham Lever in “The House of Pitt” wrote John off as “stupid and useless”. Most historians agree: he’s described, variously, as “intelligent but incurably idle” (Wendy Hinde, “Castlereagh” (London, 1981) p. 117); “charming and indolent, slightly over-burdened by the weight of his illustrious name … an incompetent general and a wretched administrator” (Joan Haslip, “Lady Hester Stanhope” (London, 1987) p. 23); “amiable … [but] exhibited signs of a natural lethargy which proved incurable” (Robin Reilly, “Pitt the Younger” (London, 1978) p. 10)… etc etc etc, you get the idea. Even Ehrman, while he admits John “was not untalented” (damned by faint praise!), reports the rumours of John’s slothfulness, drunkenness, incapacity and so on (John Ehrman, “The Younger Pitt: The Reluctant Transition” (London, 1983) p. 379.

I’m not yet ready to write my full “John was not as bad as all that” tirade (hence this is Part One only); that will have to wait till I’ve gone through all my notes. I think it is certainly beyond any historian to suggest that John was not so laid back he was pretty much horizontal. Lots of emotions complicated his relationship with his younger brother William (…. and let’s face it, being an impoverished older brother thoroughly dependent on his younger brother’s influence must have been a weird enough inversion of normality) but jealousy did not feature much, if at all. John was quite happy to let William reap all the political plaudits. Whether things would have been different had John not had a younger brother I do not know, but he never spoke once in the House of Lords that I can find and probably would not have got involved in politics at all had his brother not dragged him in.

So yes, lazy he almost certainly was. And yet when he was appointed to the Cabinet in 1788, as First Lord of the Admiralty, he seems (judging from the newspapers) to have knuckled down to the task with some degree of diligence. Cabinet meetings were held at his house (…. OK, maybe an excuse to be able to roll out of bed and go straight to work); he is often reported at Admiralty Board meetings; he was one of the Commissioners appointed during the Regency Crisis to draw up and present the Regency Bill to Parliament. He was a regular attender of court functions (and it seems George III quite liked him), not just the fun ones but the business ones too. Not, perhaps, a picture of overwhelming zeal, but certainly not one of a complete slacker.

So where did it start to go wrong? Ehrman traces it to the summer of 1793, in other words around the time when the First Coalition assault on the revolutionary French in Flanders was starting to go rather wrong. Chatham’s navy received the blame (along with the Duke of Richmond’s Ordnance) for not supplying the army well enough. Chatham defended himself by pointing out the government had split its pins between Flanders and Toulon, and the navy could not be expected to defend both fronts equally well. He escaped censure on that occasion, but when the Duke of Portland and his followers came over to Pitt from the Foxite side in the summer of 1794 they seem to have made it an express condition that one of their own would take over the Admiralty. Pitt held out five months; in December 1794 he moved his brother to the responsibility-lite post of Lord Privy Seal. Portland Whig Lord Spencer took Chatham’s place at the Admiralty.

Over the summer of 1794 I have seen a number of reports and rumours about John cropping up in newspapers and diaries (Ehrman refers to them, as I noted above). Was the Admiralty as badly run as was suggested? I’m afraid I haven’t done enough research to tell you. Rumour had it that John attended to no business before noon, kept naval officers waiting, and never opened his letters. I haven’t managed to trace any of these rumours to anything concrete (the one about the not opening letters, which is reported in N.A.M. Rodger, “The Command of the Ocean” (London, 2004) p. 363, I have traced to one of Spencer’s underlings, writing thirty or more years after the event). Obviously they all come from people who were not on John’s side, although that fact in itself means very little. As for John, he had little or no doubt he had been stabbed in the back by the Portland Whigs; he feared for his reputation, and it seems he has been right to do so.

What to conclude, therefore? John was not a naval man in any case. He was a military man, and (after Richmond resigned in early 1795) the only military man in a wartime cabinet. He seems to have given plenty of advice on military topics even when it wasn’t his remit: Castlereagh, for example, wrote to John requesting advice on military matters in October 1805 (Castlereagh Correspondence vol 6 (London 1851), 19). Lord Eldon famously said John was the ablest man in the Cabinet, and although it seems this was a throwaway remark I doubt he would have said it had he not thought John at least slightly clever. It is Chatham’s main misfortune that his whole life was blighted by the Walcheren campaign, which he commanded in 1809 and which ended in utter failure. That, however, is quite another story.

I don’t think I need to say here that I do not think John was a waste of space. You’ve worked that out by now, and 400 pages of novel certainly suggests I find him interesting. What I think is most interesting about him— to answer the question asked by the art dealer who framed my John letter— is not what he *did*, but *who he was*. He was a man who had the good fortune, or perhaps the ill fortune, to be the eldest son and elder brother of two very famous, important and brilliant public figures. He must have lived his entire life in their shadow. I hope to bring him out a bit, and round out the “late Lord Chatham” (as he was nicknamed) as a personality in his own right.

And that’s enough blathering on. Humour me. As I said, I have a Thing.

Earl Camden on the collapse of Pitt the Elder in the House of Lords, Kent RO CKS-U840/C173/30

I have been looking for an eyewitness account of the first Earl of Chatham’s spectacular collapse in the House of Lords in April 1778 for some time, and have finally found this account from Lord Camden to his daughter Elizabeth (“dear Betsey”, as the letter begins). I know there is a longer account from Camden to Grafton elsewhere, but I have not seen it so this is as close as I get right now.

The letter is dated 9 April 1778, so two days after Chatham collapsed. Camden starts with some inconsequential gossip and platitudes (“the plumbs were excellent”) then moves on to the meaty stuff. Camden was present on the occasion: Chatham went to the House of Lords to oppose the Duke of Richmond’s motion for peace with America, and suffered from a stroke halfway through.

Camden writes:

“All our hopes of any material Change of Ministry are checked at once by the fatal Accidt. that happen’d on Tuesday Last in the House of Lords by a sudden fit that seiz’d the E. Chatham just as he was rising to reply to the D. of Richmond. You may conceive better than I can describe the Hurry & Confusion the Expressions of Grieff & astonishment that broke out & actuated the whole Assembly. Every man seemed affected more or less except ye E. of M[ansfield] who kept his seat & remained as much unmoved as the Poor Man himself who was stretch’d Senseless across a Bench. He continued some time in that posture till he was removed into the Painted Chamber. Assistance was sent for in an instant, & Dr Brocklesby was the first Physician that cd be got. In about an hour Addington [Dr Anthony Addington, Chatham’s personal physician] came, & soon after the Earl [revived?] the first Symptom of life being an Endeavour to reach, wch at last had its effect by discharging a Load from his Stomach wch probably was the Occasion of the fit, for it was actually no Apoplexy, but in truth very similar to that Seizure wch took him the beginning of last Summer, for all the Appearances were the same in both. He recover’d, if you remember, from the first very soon; & was better afterwds than we had seen him for many years. I pray to God this may have no worse Consequence. He was carry’d that Eveng to Mr Strutt’s in Palace Yard, where he still remains & is this day to be removed to Serjeant’s in Downing Street. He recover’d his Senses perfectly that Eveng & slept remarkably well. He continued well all yesterday & I hear he slept this morng till ½ past 6 o’clock. I hope the best, but according to my desponding temper, I fear the worst.”

Camden was right to “fear the worst”: Chatham never fully recovered and died on 11 May 1778.

More about John in Quebec

John was still in Quebec when war broke out between Britain and revolutionary America in April 1775. He remained there for most of the first year of the war, but it gradually became clear that his presence so close to the theatre of war was undesirable on political grounds. Lord Chatham was a prominent political figure and there was some fear that John might be captured and used as a pawn to extract concessions from Britain—a fear that was nearly realised when John and General Carleton narrowly escaped capture by Canadian sympathisers with the Americans in the autumn of 1775. John’s presence in Canada was certainly well known to the American military commanders: General Washington wrote in Benedict Arnold’s instructions for invading Canada that “if Lord Chatham’s son should [still] be in Canada, and in any way should fall into your power, you are enjoined to treat him with all possible deference and respect.”

With an American invasion of Canada imminent, the decision was made to withdraw John from Canada. John seems not to have had any say in the decision: it was his mother, Hester, Countess of Chatham, who came to the conclusion that John was better out of the army. Lord Chatham was at the time suffering from one of his periodic fits of depression complicated by gout.

The following letters on the subject were written by Hester to her husband’s cousin, Lord Camelford, and are in the British Library (BL Add Mss 59490).

—-

Hayes, 7 February 1776

“I am just come from having put the question to my Lord on what his opinion was as to his Sons continuance or not in the Army. This touch’d so many tender strings that it was impossible it shou’d not agitate Him. However he gave me his decided opinion that his quitting was indispensable, and that in the present circumstances an Exchange was not a desirable Thing, as there were strong objections to his remaining in the Army, and declining to serve.” Lady Chatham therefore asks Thomas Pitt to tell Lord Barrington of “Pitt’s Resignation, in the following Words, `That the continuance of the Unhappy War in America makes it necessary humbly to request Permission of HM for Lord Pitt to resign his Commission’”.

Hayes, 8 February 1776

Lady Chatham is not pleased that “our Son shou’d sacrifice a Profession that is agreeable to Him, and in which we might flatter ourselves He might have some success”. The decision was “very unpleasant”, but she is “compensated only by the Persuasion that there is a Propriety and Fitness in the doing it”.

—-

Poor John, who was never really able to pursue a career of his own independently from his father or brother…

From the Hoare MSS, PRO 30/70/5 f. 345

Here’s a gem I discovered in the Hoare MSS (a kind of add-on to the Chatham Papers at the National Archives) a while back: a glimpse of John’s military life while he was stationed in Quebec from 1774 until early 1776. John was a lieutenant in the 47th Foot and served as one of the aides-de-camp of the governor, Sir Guy Carleton. The letter is written to Lord and Lady Chatham (John’s parents) by J. Wood, presumably John’s valet. I’ve left the English largely as spelled by Wood, so bits may have to be read aloud! (Preferably with a Zomerzet accent!)

—-

Quebec, 13 November 1774

Pleas to acquaint My Lord & Lady my Lord Pitt, is perfectly well, and has been so ever since he left England, his Lordship is not grown much in high, but is spread much thicker which I think his Lordship looks better for, the only inconvenience attends it, is his Cloaths being to little, and have no remedy but letting them out, as thair is no new Regimentals to be got at Quebec, & I will Venter to take the liberty of acquainten my Lord & Lady how my Lord Pitt passes his time in America, as I think it will not be disagreeable, for them, to hear, tho was Lord Pitt to no I had taken such a liberty he might be angery with me, His Lordship is up every morning and Dresst by seven o’clock, reads till nine, then to Breakfast with General Carleton ware his Lordship intirely Boards, attainds the Parade every Day at Eleven as that is the sure of the gard mountain, tho his Lordship his not a great deal to do thair, as the 47 regiment is not here, only som small imployments as being Addecamp to General Carleton. After his Lordship has attainded the Parade he rides or walkes if the wather will permit, if not, Reads fences or exercises with the firelock as he is learning the Exercise of the regiment that is here, as it is different from the Twentyth. His Lordship has been drest and at the Chateau, every day by a Quarter of hour before Dinner time, thare has been generally every week two large entertainments at the Chateau so that his Lordship sees a great deal of different Company. But Quebec is rather dul for his Lordship at present as greatest part of the Military Gentleman is gon to Boston, His Lordship has frequently dined with Major Calwell who lives two Miles from this town, General Carleton and Lady Marria’s [Carleton’s wife] politeness to my Lord Pitt when on board of Ship, and here, is very Great, as they never think they have all their family when my Lord Pitt is not there, I am afeard I shall take to great a liberty in given so long account of my Lord, so that I will conclude with begin leaf to offer my Duty to my Lord and Lady, Lady Hester Lady Harriot, Mr Pitt & Mr James Pitt, pleas to acquaint Mr James Pitt I have not seen any Soldier, in America, that is able to Exercise any Thing like so well as Serjeant Rogers [? I have NO idea what this is about], The wether upon the whole has been very fine ever since we landed here, but know growes rather cold, Heavy rains and a great deal of snow is daily expectd, notwithstanding the severity of the whether every body here perfers winter before Summer, after the snow is down and the frost thoroughly Seting. My Lord Pitt Desires to have sent by the first Ship that Sails for Quebec, Cloath & Buttons & other trimmins for two sutes of Regimentals, with two Epaulettes to each Coat, doe or buckskin to make two pair of Rideing Breeches a new saddle and bridle with bit and Burdoon the same as what his Lordship youst to ride Serjeant in, to send 20th of Pipe Clay, for cleaning of Cloaths.

Pleas to make my best Complits. to Mrs Sparry [the Pitt children’s nurse] Mr Willbeir [former colleague of Lord Chatham and tenant on the Hayes estate] & to all friends at Hayes from your affectionate friend

J Wood