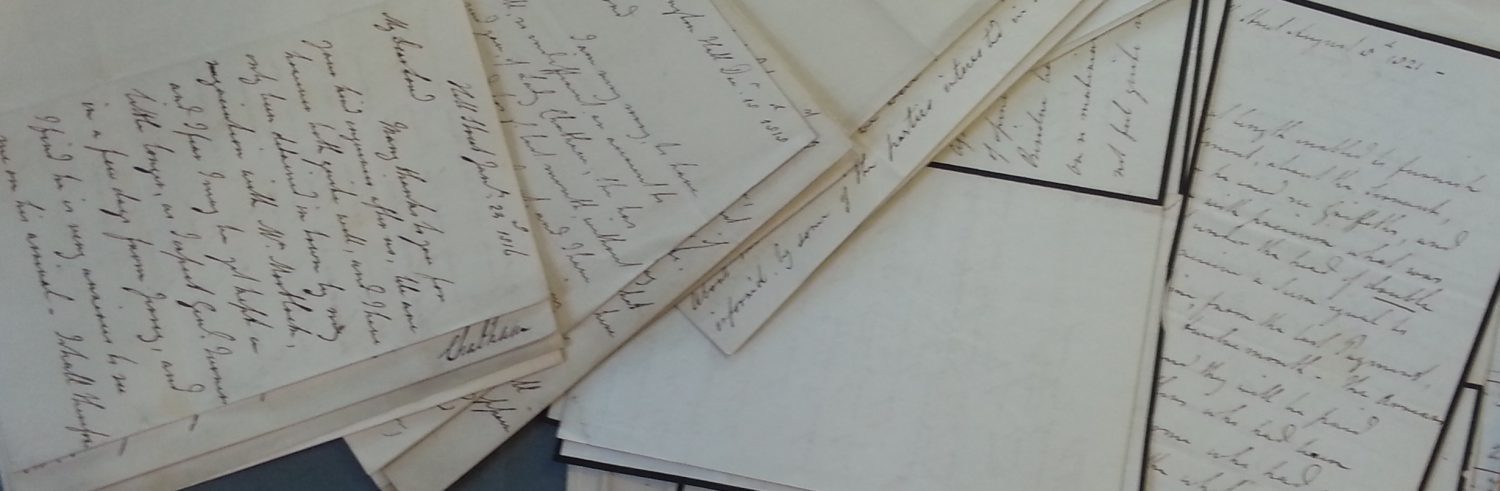

I have been looking for an eyewitness account of the first Earl of Chatham’s spectacular collapse in the House of Lords in April 1778 for some time, and have finally found this account from Lord Camden to his daughter Elizabeth (“dear Betsey”, as the letter begins). I know there is a longer account from Camden to Grafton elsewhere, but I have not seen it so this is as close as I get right now.

The letter is dated 9 April 1778, so two days after Chatham collapsed. Camden starts with some inconsequential gossip and platitudes (“the plumbs were excellent”) then moves on to the meaty stuff. Camden was present on the occasion: Chatham went to the House of Lords to oppose the Duke of Richmond’s motion for peace with America, and suffered from a stroke halfway through.

Camden writes:

“All our hopes of any material Change of Ministry are checked at once by the fatal Accidt. that happen’d on Tuesday Last in the House of Lords by a sudden fit that seiz’d the E. Chatham just as he was rising to reply to the D. of Richmond. You may conceive better than I can describe the Hurry & Confusion the Expressions of Grieff & astonishment that broke out & actuated the whole Assembly. Every man seemed affected more or less except ye E. of M[ansfield] who kept his seat & remained as much unmoved as the Poor Man himself who was stretch’d Senseless across a Bench. He continued some time in that posture till he was removed into the Painted Chamber. Assistance was sent for in an instant, & Dr Brocklesby was the first Physician that cd be got. In about an hour Addington [Dr Anthony Addington, Chatham’s personal physician] came, & soon after the Earl [revived?] the first Symptom of life being an Endeavour to reach, wch at last had its effect by discharging a Load from his Stomach wch probably was the Occasion of the fit, for it was actually no Apoplexy, but in truth very similar to that Seizure wch took him the beginning of last Summer, for all the Appearances were the same in both. He recover’d, if you remember, from the first very soon; & was better afterwds than we had seen him for many years. I pray to God this may have no worse Consequence. He was carry’d that Eveng to Mr Strutt’s in Palace Yard, where he still remains & is this day to be removed to Serjeant’s in Downing Street. He recover’d his Senses perfectly that Eveng & slept remarkably well. He continued well all yesterday & I hear he slept this morng till ½ past 6 o’clock. I hope the best, but according to my desponding temper, I fear the worst.”

Camden was right to “fear the worst”: Chatham never fully recovered and died on 11 May 1778.