A nice happy topic for a sunny Wednesday afternoon ;-). Possibly I ought to do this another day (because as usual, I should actually be writing the novel right now) but I feel the need to talk about this.

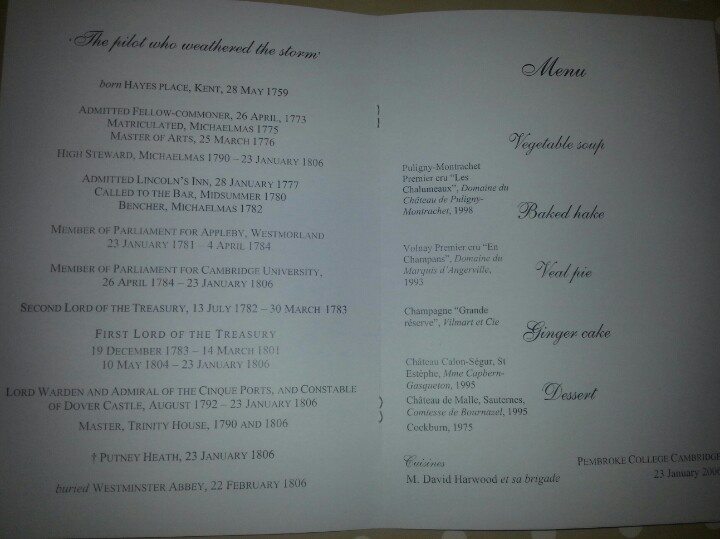

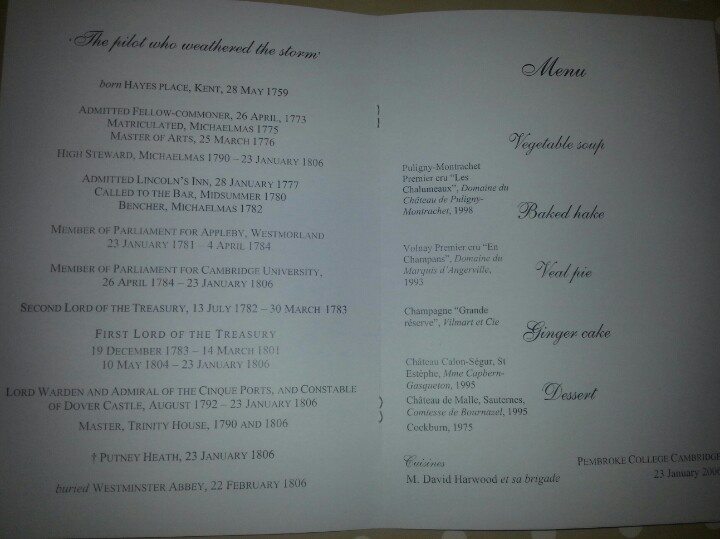

I had the good fortune to be invited to the dinner held at Pembroke College, Cambridge on 23 January 2006 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Pitt the Younger’s death. (Nothing particularly special about this, as all history graduate students working on the period were invited.) This was the menu:

I was halfway through the main course, which was rather nice, when I suddenly realised why veal pie was on the menu. Strangely nobody else seemed to have worked it out, or if they did nobody said anything.

The veal pie referenced, of course, Benjamin Disraeli’s story about Pitt the Younger’s last words. Disraeli’s story is recorded by Lord Rosebery in his “Pitt” (1891, p. 258), although had Rosebery known quite what he was starting he might have held back:

“Mr. Disraeli, in the more genial and less majestic days before 174, used to tell a saturnine story of this time [Pitt’s death]. When he first entered Parliament, he used often to dine at the House of Commons, where he was generally served by a grim old waiter of prehistoric reputation, who was supposed to possess a secret treasure of political tradition. The young member sought by every gracious art to win his confidence and partake of these stores.

One day the venerable domestic relented. ‘You hear many lies told as history, sir,’ he said; ‘do you know what Mr. Pitt’s last words were?’

‘Of course,’ said Mr. Disraeli, ‘they are well known … “O my country! How I love my country!”’ for that was then the authorised version.

‘Nonsense,’ said the old man. ‘I’ll tell you how it was. Late one night I was called out of bed by a messenger in a postchaise, shouting to me outside the window. “What is it?” I said. “You’re to get up and dress and bring some of your meat pies down to Mr. Pitt at Putney.” So I went; and as we drove along he told me that Mr. Pitt had not been able to take any food, but had suddenly said, “I think I could eat one of Bellamy’s mutton pies.” And so I was sent for post-haste. When we arrived Mr. Pitt was dead. Them was his last words: “I think I could eat one of Bellamy’s meat pies.”’ (Mr. Disraeli mentioned the meat—veal or pork, I think, but I have forgotten.)”

Amazingly enough, this story of Pitt’s last words—relayed, fourth-hand, by Rosebery, from Disraeli, who had it from Bellamy’s waiter, who had it from the messenger from Putney—is believed by some to be actually true. Amusing as it may be (insofar as it can ever be considered amusing to joke about someone’s dying words) I have no doubt Disraeli either made it up, or misremembered his source. I’m not saying Pitt did not ask for one of Bellamy’s pies at some stage of his final illness, but if he did it wasn’t right at the end. The last record of him eating anything much is I think on the 18th January when he was given a choice of egg or broth. I can’t see how his doctors would have considered feeding him a whole veal pie to be a good idea, even if they would have been happy to hear him asking for one.

If veal pie did not form part of Pitt’s last words, then what did he say? Disraeli above quotes Stanhope’s original (1861) version, printed in his biography of Pitt: “Oh my country, how I love my country!” (vol IV, 382). He later altered it to “how I leave my country” upon rereading his source, and this is now accepted as standard.

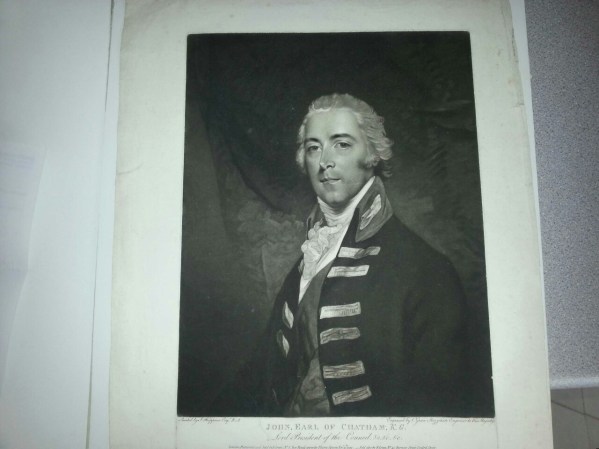

Stanhope took this from the notes written on 24 January 1806 by James Stanhope, Pitt’s “nephew” (… that is to say, the son of Pitt’s brother-in-law by his second marriage). James Stanhope was in Pitt’s room for the whole night before Pitt died and was, as far as I can gather, virtually the only person present. Ehrman in The Consuming Struggle (829, n. 2) claims Sir Walter Farquhar (Pitt’s doctor) and George Tomline, Bishop of Lincoln were in the room as well, but according to James Stanhope’s account Farquhar at least was not present (Stanhope IV, 381). George Rose, Pitt’s friend and political facilitator, recorded Pitt’s last words as “My country, oh, my country”. His authority was Pitt’s servant Pursler, who was definitely present. Farquhar, apparently, told Lord Malmesbury that Pitt’s last words were “Oh what times! Oh my country!” (Diaries of Lord Malmesbury, IV, 346). Pretty much the only person who disagreed with this version was George Canning, who decided (purely on the basis that he thought it more likely) that Pitt said “I am sorry to leave the country in such a situation”. According to Ehrman this was on Tomline’s authority, although going back to the source (Granville Leveson Gower’s Private Papers, II, 169) Canning is not reporting this as Pitt’s last words but simply as something Pitt said to Tomline before he died.

Basically, however, all sources who were present, or near, agree: Pitt’s last words, or very nearly last words, revolved around the situation of the country (and what else would he have been thinking of, I suppose? Ulm and Austerlitz had destroyed the Third Coalition, Britain was once again without allies on the continent, and Napoleon was thoroughly unchallenged). It seems clear that Pitt did say something of the sort on his deathbed.

Why, then, am I rather sceptical?

I think it is probably due to James Stanhope’s account. Apart from Tomline’s daily (and sometimes twice or even thrice-daily) letters to his wife from Putney, kept at Ipswich Record Office (HA119/T99/26 for those who are interested — although they were in the process of recataloguing when I visited so heaven knows what call number they are using now), Stanhope’s account is the only on the spot account worth going by regarding Pitt’s death. Farquhar wrote an account many years afterwards, and numerous interested parties wrote down their recollections of the stories they were told later (Rose, for example, and Pitt’s secretary William Dacre Adams), but only Tomline and Stanhope were writing on the spot at the time. Stanhope’s account thus has to be taken at face value, and its simple, factual tone lends both poignancy and credibility. But this is what Stanhope has to say about Pitt’s last words:

“At about half-past two Mr. Pitt ceased moaning, and did not speak or make the slightest sound for some time … I feared he was dying; but shortly afterwards, with a much clearer voice than he spoke in before, and in a tone I never shall forget, he exclaimed, ‘Oh, my country! How I leave my country!’ From that time he never spoke or moved” (Stanhope IV, 382)

So according to Stanhope, Pitt had spent the night moaning and muttering incoherently, then suddenly mustered up the strength to “exclaim” his last words, before subsiding into silence. Hmmm. Is that likely to happen? Could it happen? It sounds like Pitt was lapsing into a coma, woke up conveniently to speak his last words clearly and commandingly, then returned to his coma. Could this happen? I don’t know. I have precisely zero experience of death beds (… and quite happy for it to remain that way actually).

It’s definitely credible that Pitt would have spoken about his country on his deathbed— and yet how convenient that he came out with such a quotable line! I cannot possibly be the only person who thinks it almost sounds as though the parties present got together to work out a safe, “canon” version of the last words for posterity to chew on. Although I find it hard to believe James Stanhope would have colluded with Tomline and Farquhar on this, especially as Lady Hester Stanhope, James’s sister, was always quite happy to cry humbug at Rose/Tomline et al’s attempts to sanctify Pitt’s memory.

All in all, I have nothing but a hunch to suggest that Pitt’s last words may not, in fact, have been his last words. That he said those words, or something like them, seems likely, especially as everyone who was around Putney at the time agreed on a similar version. But did he say anything afterwards? Were they spoken much earlier? Who knows? The only thing I can say for sure is this — Pitt did NOT ask for one of Bellamy’s veal pies.