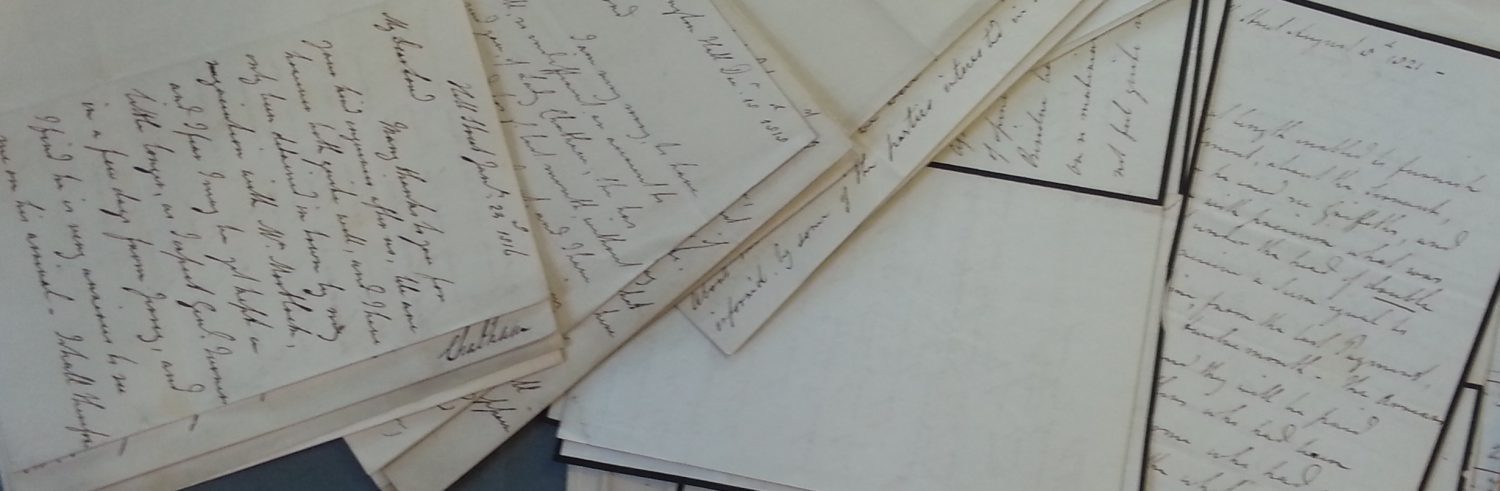

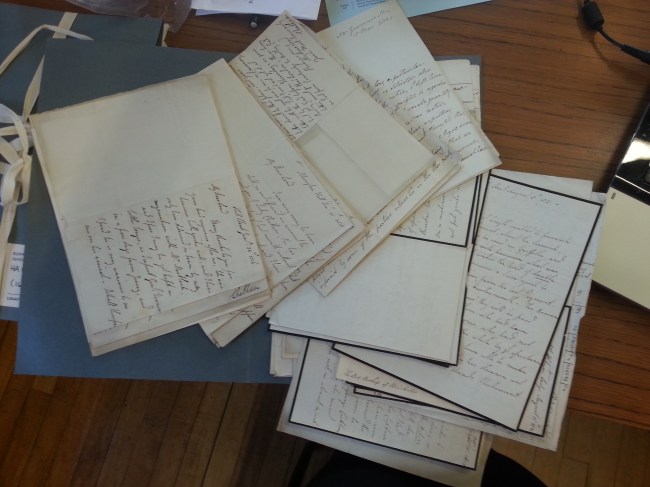

Contents of HA 119/562/688: letters from Lord Chatham to George Pretyman-Tomline, 1816-25 (Ipswich Record Office)

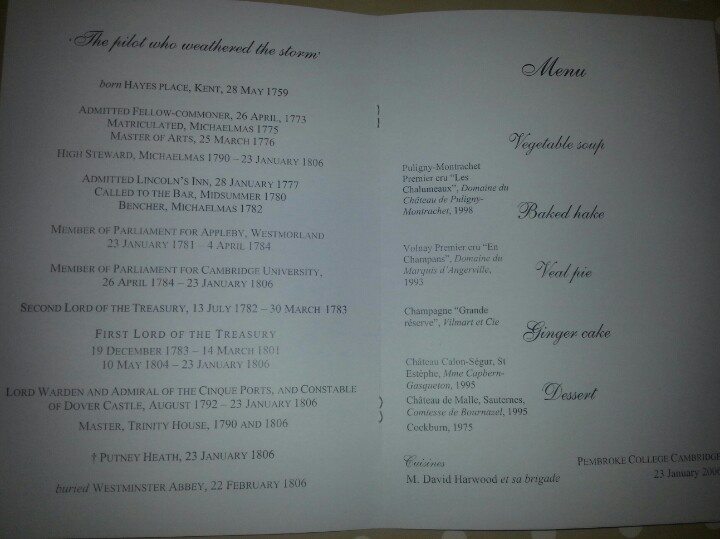

On 17 March 1818 John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham folded a sheet of foolscap, dipped his pen in ink, and began to write a difficult letter. His correspondent was George Pretyman-Tomline, Bishop of Lincoln. Tomline was an old family friend: he and John had been joint executors of John’s brother’s will and had become close over the years. Since 1816 John had been renting Abington Hall near Cambridge, which was very close to Tomline’s palace as Bishop of Lincoln in Buckden.

In writing his letter John was breaking a long silence. This was not unusual for John, who was not a particularly efficient correspondent at the best of times. As his letter made clear, however, this was not the best of times.

“I have been meditating a letter to you, for the purpose of saying, that whenever you move towards London, Abington is but a few miles out of ye road … But unfortunately I have from day to day been obliged to put off writing to you, from a cause, which I know you will be concerned to hear. Lady Chatham has now been for above three weeks extremely unwell, and still continues so. She had at first a severe bilious attack, attended with a good deal of fever, and which is not yet entirely removed, tho she is better, but it has so much reduced her, as to leave her in a very uncomfortably low and nervous state.”[1]

Six weeks later he wrote to Tomline to report the “low and nervous state” had not improved: “I had deferred writing to you … in the hope from day to day, that I shou’d have been able to have sent you a more favourable account of Lady Chatham … But I am sorry to say, that … Lady Chatham has … continued without gaining any ground”.[2]

John had no way of knowing, but he would continue to live “from day to day”, waiting for his wife to recover and return to normal, for more than two years. Mental illness is treated much more sympathetically today than it was in the eighteenth century, when it was labelled as “insanity” and treated horrifically. Rank was not proof against this: witness the treatment of George III– bled, purged, gagged, straitjacketed– in the desperate attempts to restore him to health. Ironically John’s own father, Pitt the Elder, was almost certainly bipolar, and John must have watched his wife sink into depression with a cataclysmic sense of deja vu.

John was a taciturn and deeply private correspondent; he generally kept his letters brief, factual and to the point, with perhaps a short discussion of the weather towards the end but little of a personal nature. After half a year, however, he could not keep his distress from showing, and words like “harassed” and “distressed” began to appear in his letters.[3]

In September 1818 John persuaded Mary to see Sir Henry Halford, the King’s personal physician. Halford was optimistic: a change of air was required, so John took Mary to the fashionable spa at Leamington in Warwickshire. Unable to make any plans whatsoever– still drifting “from day to day”– this was the first time John had left Abington since spring. Understandably he needed a break, but Mary was having none of it. When John suggested she stay with her brother Lord Sydney at Frognall in Kent, she insisted she was getting better. In February, nearly a year after Mary first fell ill, John finally managed to get her to Frognall. Mary’s state can best be gauged from the tone of the letter John sent to Tomline, which he only placed in the post after leaving in case the plans fell through at the last minute: “I have remained here [at Abington] in one continual state of suspense, having fixed generally one or two days every week for removing to Frognall, and having been as constantly disappointed. We now intend going tomorrow … Lady Chatham, is I am sorry to say not the least better, and my situation has been most distressing”.[5]

John was finally able to have a rest: “after the confinement I have had, I trust [exercise] will be of use to me”.[6] He certainly needed it, for apart from Mary’s family he had nobody–no children, no remaining siblings– to assist him. Over the next few months he managed to get away from Mary’s sickbed long enough to go on a few hunting parties with friends, where presumably he took out his frustration on anything that had fur or feathers. But always he returned to Mary after a week or two, and the strain of living “from day to day” was taking its toll.

By now John was beginning to guess Mary’s illness might never improve. “I fear she is losing ground,” he reported in June. In August, though, there was a glimmer of hope, and John thought she seemed a little more open to the idea of company. He wrote to the Tomlines hesitantly suggesting that “should it be convenient to you to give us the pleasure of your company … we shou’d be most happy to see you”.[7]

The Tomlines arrived on Friday 3 September. “Lady C[hatham] received us … in her usual manner,” Mrs Tomline later recorded for Mary’s physician Sir Henry Halford. All, however, was far from well, and Mary was unable to keep up the pretence of normality very long. “On Friday Evening, when Lord C[hatham] rose to ring the bell to remove the Tea tray supposing her [Mary] to have finished her tea, her eyes became frightfully wild”. As soon as she saw she was observed, however, Mary “recovered her composure– gradually became calm”.

This ability to impose self-control impressed Mrs Tomline, who noted that, “though rather Agitated, there was nothing in her manner to excite remark … We shoud have left [Abington] on Monday satisfied with this appearance of tranquillity had we judged only from seeing Lady C[hatham] in company.” But “the sad reverse, when alone” was “painful to describe”, and Mrs Tomline particularly dwelled on a disturbing conversation:

“She talked to me for some time about her illness in a way that affected me more than I chose to show. …. She was told exertion was necessary, but that she could not control herself when— and after a sudden stop, added in a wild way, ‘I must not talk of myself– but I often think it must end in madness’ – looking with eager eyes for my opinion.”

Tragically for Mary, Mrs Tomline did not recognise this as a cry for help from a desperately depressed woman. Her response was, essentially, that Mary should pull herself together:

“Of course I placed her feelings to the account of nerves & urged the absolute necessity of controuling her agitation when ever it occurred … and expressed perfect confidence that she would again recover, provided she kept herself calm, for controul in some way or other was absolutely necessary”.

Surrounded by unsympathetic listeners, Mary’s self-esteem was low and her frustration was extremely high. “She spoke with great concern of the trouble she gave Lord C[hatham] ‘to whom I am sure (she said) I ought not to give a moment’s pain’”. Having forbidden herself from confiding in her own husband, Mary found an outlet in self-harm. Mrs Tomline reported “her screams are often heard over the whole house” and how her maid had “to prevent the poor Sufferer from striking herself with a dangerous force … she is indeed covered with bruises she has given herself in various ways and with various things often with clenched hands and shut teeth”. Sleep was an issue: Mrs Tomline seemed to think it was not, but John reported her staying in bed most of the day– no doubt seeing her bedroom as a refuge from the need to put on a pretence of normality. She was certainly suicidal: “her threats respecting her own life are most alarming”.[8]

Something had to be done. John had never been robust, and his health was poor. “He cannot much longer support such a score of suffering,” in Mrs Tomline’s words. Halford’s response was not encouraging. “The matter appears to me to be coming to a Crisis,” he wrote, “and I can scarcely suppose that many weeks more will pass before the poor Creature is put under restraint.” His recommendation was to straitjacket the patient to save her husband’s health, for “it will be well if ever we see him Himself again”.[9]

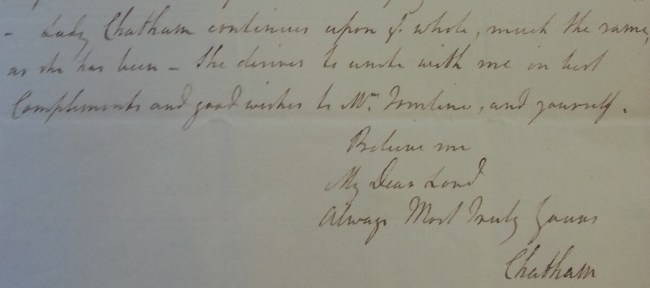

John was horrified. He had spent eighteen months nursing his wife, and was amazed at Halford’s diagnosis: “I am at a loss to understand to what he coud allude … when he spoke of any Crisis to be expected in a few weeks”. He dreaded the idea of “any change of System, unless it were deemed indispensable”, and naturally feared the effect of such “severity and cruelty” on his wife, particularly, as he saw it, to little purpose. To his credit he never referred to his wife as anything other than just that– no subhuman “poor Creature” such as is found in Halford and Mrs Tomline’s letters– and invariably passed her best compliments to Tomline at the end of his letters. Even when Mary’s state was clearly poor, he always wrote of “we” rather than “I”. But however much he disapproved of Halford’s recommendations, John was desperate. Under pressure from Halford and the Tomlines, and half-staggered under the burden of Mary’s illness, he agreed to appoint a “companion” who had experience with insanity.[10]

This “companion” was intended to impose “a restraint which the presence of Lord C[hatham] no longer produces”,[11] but it may not have worked. In the new year Mary was “very unwell, so much so, as to render her state, a very anxious one for a couple of days”, and John morosely reported to Tomline that “her state of irritation seems rather encreased”. Had Mary attempted suicide? John’s letter is ambiguous, but perhaps it is significant that they were immediately visited by their niece, Harriot Hester, Lady Pringle, who had lived with them for three years prior to her marriage in 1806. At any rate he managed to get up to Belvoir to hunt with his former ward the Duke of Rutland in February, “for I stand much in need of some recruiting having passed a sad time here”.[12]

After that the correspondence breaks off until July 1821, when John reports, on black-edged paper, that he cannot attend George IV’s levee as “there is an Order for no Person, to appear in mourning, which precludes me”.[13] John was in mourning because Mary died on 21 May, aged 58. Her obituary in the paper simply states that she died at five o’clock in the evening “after an indisoposition of nearly two years”.[14]

Mary’s physical health had never been good, so it is possible she died of natural causes, but given her history and her age I cannot help wondering if she helped herself along a little. This is obviously speculation, and John never refers to her in his letters again. I’m not sure I will ever find out the answer for certain, but whatever the truth Mary’s last years were neither happy nor healthy.

So ends the tragic tale, at least for Mary. John was destined to outlive her fourteen years; his adventures can be read about in a previous blog post of mine in two parts, found here and here. He never complained of loneliness but there is more than an echo of it in his last letters to the Tomlines before leaving England to take up the governorship of Gibraltar in October 1821: “I have been but indifferent, indeed I cou’d not well expect otherwise”. “I can not say much for myself,” he wrote the following year. “I am tolerably well in health, but I do not gain much ground, otherwise … There is a great deal of constant business [as Governor], which occupies my mind, and from this, I think I have found most relief”.[15]

Poor Mary, and poor John. It’s no secret that I feel a strong bond with these two; they are, after all, the main characters of my work in progress. But until yesterday I had no idea their story ended so tragically. I cannot tell you how much I wish it had been otherwise.

References

All manuscripts are from the Pretyman-Tomline MSS, held at Suffolk Record Office (Ipswich).

[1] Chatham to Tomline, 17 March 1818, HA 119/T108/24/7

[2] Chatham to Tomline, 24 April 1818, HA 119/562/688

[3] Chatham to Tomline, 14 October 1818, HA 119/562/688

[4] Chatham to Tomline, 18 December 1818, HA 119/562/688

[5] Chatham to Tomline, 1 February 1819, HA 119/562/688

[6] Chatham to Tomline, 19 February 1919, HA 119/T108/24/8; same to same, same date, HA 119/562/688

[7] Chatham to Tomline, 2 June, 17 August 1819, HA 119/562/688

[8] Mrs Tomline’s letter to Sir Henry Halford is at HA 119/562/716. John’s observations on Mary’s lying later in bed are from HA 119/562/688, 22 and 27 September 1819

[9] Sir Henry Halford to Mrs Pretyman, 10 September 1819, HA 119/562/716

[10] Chatham to Tomline, 22 September 1819, HA 119/562/688; 27 September 1819

[11] Mrs Tomline to Sir Henry Halford, HA 119/562/716

[12] Chatham to Tomline, 19 January 1820, 5 February 1820, HA 119/562/688

[13] Chatham to Tomline, 25 July 1821, HA 119/562/688

[14] The European Magazine and London Review 1821, vols 79-80, 561; The Ezxaminer 1821, 335.

[15] Chatham to Tomline, 6 October 1821, 27 February 1822, HA 119/562/688

Picture of Abington Hall from here.

Picture of Sir Henry Halford from here.