About a year ago I did a considerable amount of research on the Anglo-Russian Helder expedition of 1799 (you can read more about that here). John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham had returned to his military career in 1798, and was appointed to the command of the 7th Brigade in the expedition. My novel follows him to Holland, and last week I finally got the opportunity to do some location research. My husband and I hired a tandem, took a train from Amsterdam to Den Helder, and cycled through the most important locations associated with the campaign.

Day One: Amsterdam – Den Helder – Callantsoog – Schagerbrug – Schagen

The train up to Den Helder was instructive. We sat with a friendly and chatty local who was interested to hear the purpose of our visit and helpfully pointed out a number of towns from the train window as we travelled up. My impression was of comparatively small, tight towns interspersed by long stretches of flat countryside. We passed through Castricum, Alkmaar and Schagen before finally arriving at Den Helder, in 1799 Holland’s northernmost point ….. about at the same time as the thunder.

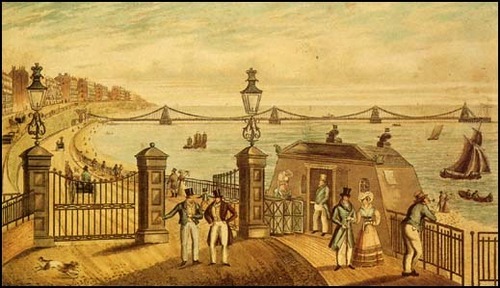

We set off as swiftly as we could, getting briefly lost in town while I got used to our map. At last we found the coastal cycle path, cycling up a steep incline to reach the top of the dyke surrounding the seaward-side of the town. From here we paused to take in the beautiful view towards the island of Texel: a significant strategic point for the navy in the 18th century.

Shortly after I took the above photograph, the heavens opened with an almighty peal of thunder. I was at first quite glad about this — the 1799 Helder expedition was plagued by bad weather, and I had hoped to have the “full Helder experience” for at least a little while — but there was a strong south-easterly wind and, after a few minutes, we had to stop cycling because neither of us could see. Honestly I never knew rain could actually be painful. Even standing still it felt like being repeatedly whipped in the face by a wet pincushion. (At least it was warm!)

Eventually the rain died down, but did not completely stop all afternoon. Still, at least we were able to cycle on, passing Kirkdijn Fort (1811, I believe) and turning southwards down the side of the coast towards Callantsoog.

I did not take too many photographs at this point, because any attempt to stop made us cold as well as wet. Luckily the tandem we had hired was a complete tank, built for city use rather than up-and-down coastal paths, complete with a dicky first gear which (after getting stuck in it a few times) we avoided using unless utterly necessary.

By this time we were entering the dunes. These run down the majority of the Helder peninsula coast, separating the flat mainland from the turbulent sea. Most of the 1799 Helder fighting took place in this terrain, so I was very interested to see it. Now it is a nature reserve, but I doubt it has changed a great deal in 200 years. The sand was quite dense and held together with scrub. Cows and sheep roamed everywhere. Whenever we joined the roads we saw little draining canals everywhere, criss-crossing the countryside in all directions.

What with the rainfall making the roads slick with water I could see why some British soldiers, retreating at the end of the campaign in torrential rain, occasionally mistook the canals for roads and fell in.

In mid afternoon we reached Keeten near Callantsoog, where the British made their first landing on Dutch soil on 27 August 1799. They were immediately challenged by the Dutch General Daendels, whom they beat back on a narrow strip of beach only wide enough for one battalion to face front at a time. It was the first pitched battle of the campaign and set the tone for the rest: short, sharp and bloody. The sand was very difficult to walk on, soft and giving way underfoot. I cannot imagine how hard it must have been for the British, who had to wade up through the surf to the beach, probably still feeling seasick, then fight their way inland.

By now we were sopping, so we hastened to our destination for the night: Schagen. On the way we passed through Schagerbrug, a tiny hamlet which (as the name suggests) consisted mostly of a bridge over the North Holland Canal, a church, and … er … that’s about it. For some reason Schaberbrug was the Duke of York’s first headquarters as Commander in Chief of the Allied British and Russian army. No clue where he stayed but I did not have time to hang around and search as the weather was so awful. I have no idea why York chose Schagerbrug as his HQ when Schagen, a much larger market town, was only just down the road (can anyone enlighten me?) but I paused only to take a photograph or two.

We arrived at Schagen shortly afterwards. Schagen is a much bigger place than Schagerbrug, a collection of traditional Dutch brick houses with the stereotypical step-faced fronts clustered around a beautiful church. We stayed in the Castle, which it turns out was used as a barracks for British soldiers in 1799. Unfortunately the Brits trashed the joint and the castle was largely demolished in 1819.

This was, incidentally, the only place where I saw a plaque commemorating the 1799 Helder campaign.

Day Two: Schagen – Schoorl – Alkmaar

The next day was dry! Hallelujah! We were glad about this, as we had both had enough of the complete 1799 experience and our shoes were still wet. We set off about eleven across the flatlands back towards the coast, cycling largely along the top of dykes and alongside the canals veining the flat “polders” landscape.

We were making for Schoorl at the base of the dunes. Our objective was to follow, as much as possible, the route John, Lord Chatham would have taken with his brigade on 2 October 1799 during the battle for Bergen (alas we ran out of time and were not able to visit Bergen itself, but I do not think John set foot there either). Chatham was attached to General Dundas’s brigade and tasked with acting as a reserve force for the Russians. The Russian force did most of its fighting in the towns of Schoorldam and Schoorl, but, once they had cleared Schoorl of French, refused to proceed to take Bergen. British General Coote said the Russians lay down on the ground and refused to get up when he ordered them to march.

Chatham’s brigade then marched into the sand dunes to assist General Dundas, whose battalions had become scattered in the terrain. Chatham’s men helped form a stronger line and, under strong fire from French artillery in the trees on top of the sand dunes, cleared the field of enemy.

We cycled in the direction I guessed John would have taken his men. The countryside was, as before, perfectly flat, but before long the dunes loomed ahead of us on the horizon.

The terrain here is quite different from northern Helder: heavily wooded, with the most enormous, steep, impressive dunes. The ones at Schoorl were the biggest of all, between 150-200 feet high. Forget everything you’ve ever known about dunes: these were BIG, like small mountains with a couple of kilometres worth of undulating landscape on top covered with trees. I immediately began to appreciate why all eyewitness accounts of the campaign laid such stress on the “intricate” nature of the landscape.

On top of the dunes, the trees were very dense. I got the impression many of them had been planted since 1799 — they were predominantly pine, and I seem to recall contemporary accounts described mainly beech and birch — but I could easily see how the French could launch ambushes from the trees on attacking troops, and there were so many tree-roots criss-crossing the ground it must have been extremely difficult to march up the sandy ground.

The terrain flattened out a bit here, but remained undulating for several kilometres towards Bergen. I immediately realised how easy it would be to lose whole brigades in such terrain. The fact that the British seemed to have completely lost sight of whole branches of their force no longer surprised me.

We knew there had been forest fires in the Schoorl area within the past five years, and there were unfortunately still signs that the landscape is recovering. It appears the fires were started by arsonists. Many trees were blackened stumps and a lot of the terrain still smelled strongly of ash.

The second half of our journey through the dunes took us past Egmond-aan-Zee, in 1799 known as Egmont-op-Zee. The worst of the fighting on 2 October took place in the dunes around Egmont, where Sir Ralph Abercromby came to grips with the bulk of the French and Dutch armies defending Bergen. The dunes here are less tall than near Schoorl, but much denser. Eyewitness reports suggest it was very difficult for the British to form up in their traditional lines, and the fighting got very bloodthirsty:

We marched forward … to a place where … the sand rose pretty high, in the form of a semicircle; into this opening we wheeled, and were instantly exposed to a fire upon both our flanks and front … We continued to stand still and fire for a few seconds, and then began to move forward, firing as we advanced; the other two divisions had wheeled into various openings in the sandhills in our rear …

In some instances, parties of our troops came suddenly ipon parties of the enemy. In one instance, one of our parties haveing climbed to the top of a sand ridge, found that a party of the enemy was just benearth, and instantly rushed down the ridge upon them; but the side of the ridge was so steep and soft, that the effort to keep themselves from falling prevented them from making regular use of their arms. They were involuntarily precipitated amongst the enemy, and the bottom of the ridge was so narrow, and the footing on all sides so soft, that neither party were [sic] able, for want of room, to make use of the bayonet; but they struck at each other with the butts of their firelocks, and some individuals were fighting with their fists. (Narrative of a private soldier in His Majesty’s 92nd Regiment of Foot … (London, 1820) pp 46-7)

This part of the trip was quite amazing. Some of the landscape was truly astounding. For some reason I seem to have lost the photos I took though, so you’ll have to extrapolate based on the shots I took above, and this short video I took while cycling through the landscape:

We arrived in Alkmaar early in the evening, and went straight to our hotel. Alkmaar was the Duke of York’s second headquarters after the successful push on Bergen on 2 October, when the British line moved forwards closer to Amsterdam. I will, however, cover that in greater depth in my next post, when I will conclude the account of our trip to Den Helder.