In 1818 George Pretyman-Tomline, Bishop of Lincoln, Pitt’s old friend and executor, was putting the finishing touches to the book that would later be published in part as the first official biography of Pitt the Younger. He sent his draft to various of Pitt’s friends and connections to read over. One of them was Lord Grenville, Pitt’s cousin and former Foreign Secretary.

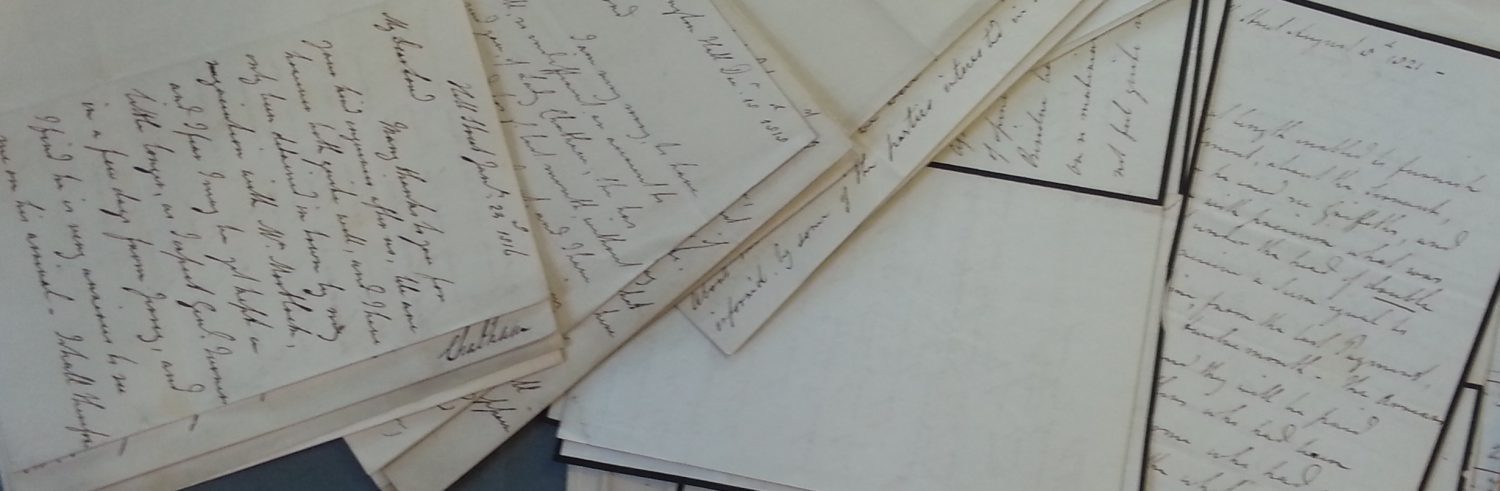

Grenville sent back a lengthy critique of the work. He included some interesting thoughts on the role of parliamentary reporting during Pitt’s time as prime minister. His fear (not entirely unreasonable) was that Tomline’s heavy reliance on official publications such as the Parliamentary Register would affect the public’s view of Pitt’s oratory, and consequently of his opinions. Grenville’s point, essentially, was that parliamentary debates were inaccurately reported. The following is from the Stanhope MSS in Kent RO, U1590/S5/O12.

“I lament to think how much your work will tend to accredit an error already much too prevalent. The practice of reporting the Parliamentary debates from day to day is as you know an innovation of our own times, & one of most extensive consequence both good & evil. At first it was pretty generally understood how very inaccurate such representations are, & must necessarily be. By degrees a contrary impression is taking possession of the public mind, & it is now commonly said, even by those who ought to know better, that these reports though not correctly accurate, are yet, substantially, fair representations of the opinions & arguments which they purport to convey. This opinion is in itself quite erroneous; it is destructive of the truth of history, highly injurious to all public men, &, as it happens, most paticularly so to Mr. Pitt, & those who acted with him in his first administration.

It is impossible that such reports can be even substantially accurate. What justice can a reporter, with the most upright intentions, do to the opinions or reasonings of statesmen on subjects which they have deeply studied, & of which he is often entirely & completely ignorant? What report could you or I make of a pleading in Chancery, a debate in the College of Physicians, or of the deliberations of a Council of War on the attack or defence of a place of which we never even saw a map? Just such are the reports of newspaper reporters, on Plans of Finance, on Measures of Revenue or Commerce, or foreign treaties of trade, alliance, or war, and on legal & constitutional questions of great intricacy, & deep research.

This is true, even if we admit on the part of the Reporter the impartiality of a Judge, & the attention of a sworn Juryman. But you surely must remember that, for reasons too long to be here detailed, there was a considerable period, during which no such impartiality existed towards Mr Pitt & his friends, in the Mass of those who were concerned in these reports. … Justice was rarely, if ever, done to him & to his cause.”