The Walcheren Expedition of 1809, which Lord Chatham infamously commanded, was unquestionably a disaster. Although the British managed to take the islands of Walcheren and South Beveland, they failed to get to Antwerp, the ultimate objective, to destroy the fortifications there and the French and Dutch fleet.

Most seriously of all, the army was rendered completely useless by a violent illness known as “Walcheren Fever”, thought to be a combination of malaria, typhoid, typhus and dysentery. Of the 39,219 men sent to the Scheldt River basin, 11,296 were on the sick lists by the time the inquiry was underway. 3,960 were dead. The British Army suffered from the recurring effects of “Walcheren fever” until the end of the war.

Not long after the last soldier had been landed back in Britain in January 1810, the House of Commons formed itself into committee to inquire into whose bright idea it had been to send nearly 40,000 of Britain’s best (i.e., only) troops to a pestilential swamp at the height of the unhealthy season.

Careers were at stake, and nobody wanted to own up. Chatham, the military commander, was nevertheless pretty sure he knew who was most to blame for what had happened. Unsurprisingly, it wasn’t him. Contrary to what nearly every historian of the campaign has tried to argue, however, it wasn’t his naval counterpart, Sir Richard Strachan, either.

Chatham wasn’t very successful at fighting accusations of his sloth and incompetence, and he eventually ended up with most of the blame for the campaign’s failure, even if the Walcheren inquiry technically cleared him of wrongdoing. In my opinion, however, one aspect of Chatham’s evidence has been overlooked: his indictment of the Board of Admiralty, under the First Lord, Earl Mulgrave.

Lord Mulgrave

After the inquiry was over, Chatham wrote a series of memoranda defending his conduct on Walcheren and during the parliamentary proceedings that followed. These memoranda reveal Chatham’s conviction that Mulgrave had been trying to cover up the Admiralty’s role in planning the expedition for months.

By April 1810, when he probably wrote these memoranda, Chatham was as paranoid as it is possible for a man to be. Nor was he the least bit impartial in the matter. And yet there is some evidence that the Admiralty – a highly organised political body, and one with which Chatham (a former First Lord himself) was extremely familiar – did indeed try to conceal evidence from the inquiry.

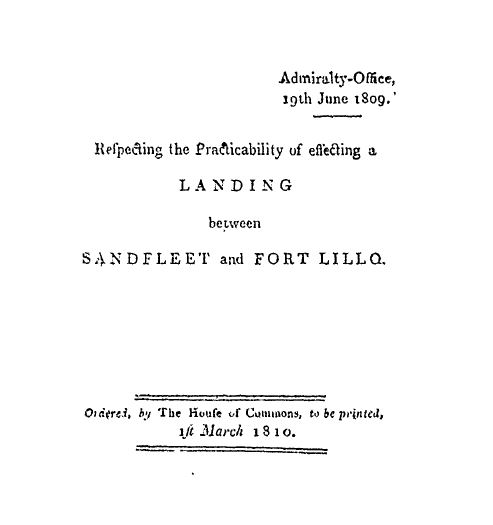

One very important piece of information was only laid before the inquiry at all on 1 March 1810, and only because Chatham’s testimony had drawn public attention to it. This was a memorandum, written on 19 June 1809 at the Admiralty Office, entitled “Respecting the Practicability of effecting a Landing between Sandfleet [Sandvliet] and Fort Lillo”. (Sandfleet, or Sandvliet, being the place where the British Army was meant to land on the continent, nine miles from Antwerp; Lillo being one of the two forts straddling the point at which the Scheldt River narrowed before the dockyards.)

The belatedly-published memorandum quoted two naval officers, Sir Home Popham (one of the planners of the expedition) and Captain Robert Plampin, both saying they had both been to Antwerp in the 1790s and thought there would be no problem in landing a large body of men between Lillo and Sandvliet. On that basis, the Opinion made the following statement:

The belatedly-published memorandum quoted two naval officers, Sir Home Popham (one of the planners of the expedition) and Captain Robert Plampin, both saying they had both been to Antwerp in the 1790s and thought there would be no problem in landing a large body of men between Lillo and Sandvliet. On that basis, the Opinion made the following statement:

The Board of Admiralty having made inquiry respecting the practicability of effecting a Landing between the point of Sandfleet and Fort Lillo … are prepared … to undertake that the troops shall be conveyed, when the Island of Beveland, including Bathz is in our possession, to the Dyke between Fort Lillo and Sandfleet, and landed, as far as the question of Landing depends on the nature of the place, with relation to the approach to the shore of boats and other vessels capable of receiving troops.[1]

Why was this so mysterious? Because Chatham remembered this memorandum rather differently from the form in which it was published for the inquiry.

According to Chatham, the Cabinet had only approved the expedition in the first place after the Admiralty Board had issued this Opinion as a guarantee that a large fleet could carry twenty thousand men up the West Scheldt and land them at Sandvliet. This was in response to doubts voiced by Chatham himself – doubts formed after discussions with military officers who had been to Sandvliet and told him an army could not be landed there. Since the whole plan hinged on landing at Sandvliet, Chatham rather reasonably told the Cabinet he would not undertake to sanction his own expedition unless the Admiralty could prove the military men wrong: “This last Point I considered as a sine qua non [which] … must be placed beyond all doubt, to warrant the undertaking the enterprize [sic].”[2] Mulgrave’s response was the 19 June memorandum, which circulated through the Cabinet the day after it was drawn up.

Chatham remembered it as being signed by the three professional Lords of the Admiralty. In 1809, these would have been Sir Richard Bickerton, William Domett, and Robert Moorsom.

Chatham’s assertions are to an extent backed up by official correspondence. Following the mid-June cabinet meeting, Castlereagh informed the King of the need to postpone preparing for the expedition until “the practicability of a Landing at Sandfleet [sic] can be assured”. Two days after the circulation of the 19 June Opinion, Castlereagh wrote: “Under the sanction of this opinion … Your Majesty’s confidential servants … feel it their duty humbly to recommend to Your Majesty that the operation should be undertaken”. Castlereagh edited out the line “should the Immediate object be abandon’d”, which suggests that the viability of a Sandvliet landing was indeed the make-or-break feature – to borrow Chatham’s words, the sine qua non – of the expedition going ahead.[3]

All this corroborates Chatham’s account completely, except for one detail. Three copies of the Opinion exist, one in the Castlereagh MSS at PRONI (D3030/3241-3) and two in the National Archives (ADM 3/168). None is signed. The copies of the Opinion that remain are therefore no more than that – an opinion. They were unofficial, and could not be claimed to form the basis of any Cabinet decision to undertake the expedition.

Did Chatham simply misremember the opinion? This is the opinion of Carl Christie, who deals with the 19 June Opinion thoroughly in his excellent thesis on the Walcheren expedition. “The suspicion is that his memory was playing tricks on him”, Christie writes, and concludes that he “misinterpreted the Admiralty opinion”.[4] But Chatham clearly wasn’t the only one who did so, as Castlereagh’s letters to the King show above.

The question, therefore, is whether a signed Opinion ever existed. We only have Chatham’s word for this; but it does seem unlikely that the Cabinet would have made the important decision to proceed with the expedition on the basis of the opinion of two subordinate naval officers. (Popham in particular had a track record of leading British troops into madcap schemes that often went wrong, as the Buenos Aires expedition of 1806 demonstrates).

Castlereagh later played down the importance of the opinion: at the inquiry, when questioned about it, he seemed confused as to which memorandum Chatham had intended to single out, and fudged the issue by saying there was a paper “which I may have seen in circulation, with the names of three [Admiralty] lords attached to it, but I rather imagine that it is the same paper as that which is dated the 9th of June”. But the Admiralty opinion of 9 June 1809 was on a completely different topic, and had also been drawn up prior to the Cabinet meeting to which Chatham referred.[5]

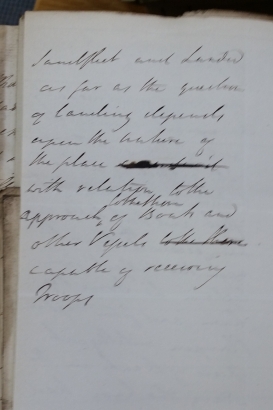

There is, however, one further possibility: that Chatham’s memory was not faulty at all, and that the opinion he saw was different from the printed version. The accusation that the Admiralty later cherry-picked the evidence laid before the Walcheren inquiry to play down its role in the planning, indeed, seems to form the thrust of Chatham’s memorandum. He did not come outright and say so, but he came close when he asserted:

An attempt was made in the course of the Enquiry, to question the existence of this Document, and they [the Admiralty] never would produce it, but they did not venture to call the Sea Lords [to give evidence], and with them the question whether they had not signed such a Paper and delivered to Lord Mulgrave, to be shewn to ye Cabinet.[6]

So where is the signed version of the Opinion the Admiralty failed to produce? Did it ever exist? Castlereagh’s evidence, vague as it was, certainly suggests that it did. Chatham was certainly convinced the Admiralty was covering its back at his expense. Was he right?

We will probably never know.

References

[1] Parliamentary Papers 1810 (89), “Respecting the Practicability of effecting a Landing between Sandfleet and Fort Lillo”

[2] Memorandum by Chatham, PRO 30/8/260 f. 100

[3] Castlereagh to the King, draft, 14 June 1809, PRONI Castlereagh MSS D3030/3137. The 15 June copy that was sent is printed in Aspinall V, 298

[4] Carl A. Christie, “The Walcheren Expedition of 1809” (PhD, University of Dundee, 1975), pp. 126, 131

[5] Testimony of Lord Castlereagh, 13 March 1810, Parliamentary Debates XV, Appendix 5xxii-iv

[6] Memorandum by Chatham, undated, National Archives Chatham MSS PRO 30/8/260 f 100