Current events in Parliament are very interesting to me as a political historian, although I admit I’d prefer to be watching from the safer distance of, say, a couple of centuries. Since I am a historian, however, and a Napoleonic-era one at that, yesterday’s triple defeat of Theresa May’s government reminded me strongly of the situation of the Perceval government over the winter of 1809–1810. Perceval’s government wasn’t exactly found to be in “contempt of Parliament”, like May’s, but it might as well have been. Here’s why.

The Perceval Government

Spencer Perceval kissed hands as First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer at the beginning of October 1809. He succeeded the Duke of Portland. At the beginning of September, it had been revealed that Foreign Secretary George Canning had been intriguing against the Secretary of State for War, Lord Castlereagh, for some months. Portland had actually agreed to force Castlereagh out and reshuffle the cabinet to accommodate Canning’s friend Lord Wellesley. The outcome of all this was that Canning and Castlereagh both resigned (and then fought a duel), while Portland – who had recently suffered a stroke and was in poor health – gave way to Perceval.

Perceval thus started out under the shadow of Canning and Castlereagh’s disgrace. His position was not improved by the fact that the Portland government’s big military campaign of the year – the Walcheren expedition, involving 40,000 troops and over 600 naval vessels – was in its final disastrous throes. The expedition’s commander, Lord Chatham, had failed to take Antwerp (his ultimate goal), and sickness was tearing through the troops. By mid-September, nearly 10,000 men were on the sick list. Most of the army was recalled, but a garrison of 16,000 men under Sir Eyre Coote remained on Walcheren, pending further orders.

Matters were made even worse by the fact that Lord Chatham, the expedition’s commander, had also been a member of Portland’s cabinet as Master-General of the Ordnance. This was a huge millstone around Perceval’s neck; indeed, many cartoons depicted Chatham at this time with a large millstone inscribed “WALCHEREN”.

(From here)

Perceval spent several weeks putting his government together. He approached the leaders of the opposition, Lord Grenville and Earl Grey; he approached former prime minister Lord Sidmouth, who had a reasonably sizeable political following. They all refused to join him. With Canning and Castlereagh both out of the question, Perceval found himself having to fall back largely on the same ministers who had served in the discredited Portland government. Even Chatham got to stay on at the Ordnance.

These attempts to shore up an already-tottering government took up most of Perceval’s attentions, and it was only in November that the cabinet finally got around to discussing what to do with Walcheren (meanwhile, half of Coote’s garrison there had fallen ill with fever). Walcheren was finally evacuated at the end of December.

Inquiry: political or military?

Perceval was aware he would face an immediate onslaught from the opposition in Parliament on Walcheren. He knew there was no way he would be able to avoid some sort of political scrutiny, particularly after the extremely influential London Common Council (representing London’s considerable mercantile interests) laid an Address before the King calling for an inquiry into the debacle. A year previously, the Portland government had managed to dodge a similar bullet over the dire military situation in the Peninsula by placing the responsible army commanders (including the future Duke of Wellington) before a military inquiry at Chelsea – despite calls from the City of London for a political investigation. Perceval knew he would not be so lucky now.

Since an inquiry was inevitable, the only question was what form the inquiry should take. Perceval hoped he would be able to limit any damage to his government by restricting an inquiry to a select committee, which would only be obliged to publish its ultimate decision and not its full proceedings. Effectively, Perceval wanted to control the evidence that would be laid before Parliament (and the public).

Perceval managed to put the meeting of Parliament off over Christmas, but when Parliament met again on 23 January 1810, the opposition went straight to the attack. On 26 January, Lord Porchester led the opposition in its demand for a political inquiry – not a select committee, but a committee of the whole House of Commons (a format that had recently been used for assessing evidence that the Duke of York, as Commander in Chief, had been selling military commissions through his mistress, Mary-Anne Clarke).

Lord Porchester

The opposition hoped this format would do two things – indict the government before the eyes of Parliament and the people, and force the government to produce and publish all the relevant paperwork, rather than cherry-picking their evidence. As Porchester argued, the nation at large had a right to know how the government was using its military resources:

I cannot consent to delegate the right of inquiry on this occasion to any select or secret Committee, by whom the course of investigation might be misdirected, or its bounds limited – before whom, possibly, garbled extracts, called documents, might be laid by ministers themselves, in order to produce a partial discussion … It is in a Committee of the whole House alone, we can have a fair case, because if necessary we can examine oral evidence at the Bar.[1]

In other words, Porchester and the opposition were putting the government on trial before the House of Commons – and, by extension, the people.

The government is defeated (repeatedly)

Perceval tried to deflect Porchester’s motion for an inquiry of the whole House by moving the previous question (effectively an attempt to dispose of the motion altogether), on the grounds that a select committee would be more suitable. He found himself deserted by a number of his supporters, including Lord Castlereagh, who (as former Secretary of State for War) welcomed an inquiry into the expedition he had planned, hoping it would clear him; and the Commons supporters of Lord Chatham, who hoped an inquiry would uncover the duplicity of his colleagues in sending him on the expedition with insufficient (and perhaps even false) information.

Perceval first tried to adjourn the debate until 5 February; he was defeated without a division. The previous question was then put, and the opposition carried the day 195 votes to 186. The government was now committed to a full inquiry of the sort they had been dreading. The inquiry began on 2 February 1810; all its proceedings were published, in the newspapers and in the official parliamentary debates (the future Hansard).

Despite the best hopes of the opposition, the government managed to weather the Walcheren storm and did not fall. After the government’s defeats on 26 January, nobody had really been expecting it to survive the inquiry. It nearly didn’t, particularly when it became clear that Lord Chatham had (apparently) submitted a private narrative defending his conduct at Walcheren to the King – an unconstitutional act.

At the end of February 1810, the government was again defeated in the lobbies and forced to produce more written evidence. On 23 February, oppositionist Samuel Whitbread moved that all papers in the Royal archives relating to Chatham’s narrative should be produced; his motion was narrowly passed by 178 to 171. Whitbread then moved two resolutions on 2 March censuring Chatham’s conduct. Perceval was once more unable to move the previous question and throw Whitbread’s censures out without a debate; he lost 221 to 188, with many supporters once again in the Noes lobby. Only an amendment by George Canning (then a backbencher) softened Whitbread’s language and passed without a division, but Perceval had been unable to protect a member of his own government. Only Chatham’s resignation from the cabinet on 7 March prevented the government falling with him.

George Canning

The outcome

On 26 March, Lord Porchester moved eight resolutions censuring the ministers:

The expedition to the Scheldt was undertaken under circumstances which afforded no rational hope of adequate success. … The advisers of this ill-judged enterprise are, in the opinion of this House, deeply responsible for the heavy calamities with which its failure has been attended. … Such conduct of His Majesty’s advisers, deserves the severest censure of this House.[2]

The resolutions were discussed by the House of Commons over the course of four bitter days. The opposition had been expecting to force Perceval’s resignation; what actually happened was that Porchester’s resolutions were rejected 272 votes to 232 early in the morning of 31 March. The House of Commons then passed a resolution approving of the retention of Walcheren until December by 255 votes to 232.

What had gone wrong? Perceval’s most recent biographer, Denis Gray, thought Perceval’s unexpected triumph was evidence that his “courage and steadiness had pulled it [survival] off against the greatest imaginable difficulties and odds. After the Walcheren debates Pittites again new that they had a leader of resolution and character.”[3]

Historian Michael Roberts, however, gives a different answer: “The majority of independent members preferred to take the chance that Walcheren would be a salutary lesson to the Government, than to risk putting the country into the hands of a party that had neither policy, nor prospect of uniting upon one, nor ability to carry it out.” Later, Roberts reiterates the point: “The Walcheren vote was not so much in favour of the Tories as against the Whigs”.[4]

In other words, Perceval’s survival was due less to his own skill and more to the weakness of the opposition, which found it easier to criticise than to propose its own alternative agenda. Divided as it was over the issue of whether or not to commit more fully to the war in the Peninsula, and with nascent divisions between Lords Grenville and Grey, the opposition was, indeed, perhaps no more capable than the government to guide the war effort – as their brief stint in power in 1806–7 as the Ministry of All the Talents had shown.

Modern parallels?

Only time will tell of Theresa May’s government is able to hold its own, or whether Jeremy Corbyn’s opposition is capable of presenting a valid alternative political agenda. I suspect we will find out more about that over the coming week. But it struck me that the Walcheren inquiry does have some modern echoes. At any rate, it is certainly not the first time that a government has fought for its life in the face of public scrutiny.

References

[1] Parliamentary Debates volume XV (1812), col. 162

[2] Parliamentary Debates vol. XVI (1812), cols. 78–80

[3] Denis Gray, Spencer Perceval: The Evangelical Prime Minister (Manchester: University Press, 1963), p. 304

[4] Michael Roberts, The Whig Party, 1807–12 (London, 1939), pp. 147, 322–3)

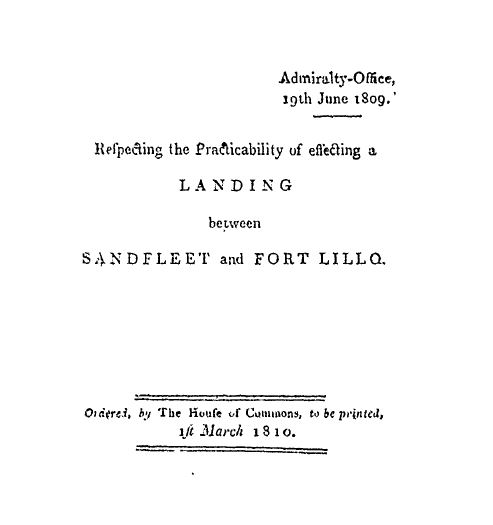

The belatedly-published memorandum quoted two naval officers, Sir Home Popham (one of the planners of the expedition) and Captain Robert Plampin, both saying they had both been to Antwerp in the 1790s and thought there would be no problem in landing a large body of men between Lillo and Sandvliet. On that basis, the Opinion made the following statement:

The belatedly-published memorandum quoted two naval officers, Sir Home Popham (one of the planners of the expedition) and Captain Robert Plampin, both saying they had both been to Antwerp in the 1790s and thought there would be no problem in landing a large body of men between Lillo and Sandvliet. On that basis, the Opinion made the following statement: